∗∗∗∗∗∗∗∗∗∗

(10/10) In a nutshell: The plot may be slightly simplistic and the political message naive, but the thematic and visual influence of Austrian director Fritz Lang’s exciting 1927 masterpiece Metropolis is rivalled by few in science fiction and in film in general. A great, entertaining, sprawling epic in a future tower of Babylon.

Metropolis. 1927, Germany. Directed by Fritz Lang. Written by Thea von Harbou, Fritz Lang. Starring: Brigitte Helm, Gustav Fröhlig, Alfred Abel, Rudolf Klein-Rogge. Cinematography: Karl Freund. Produced by Erich Pommer for UFA. Tomatometer: 99 % IMDb score: 8.3 (#106) Metascore: 98/100.

Few films have been so much written about and analysed as Austrian director Fritz Lang’s stupendous epic Metropolis. Not only is this dystopian sci-fi classic with political and religious undertones one of the most influential sci-fi films of all time. It is also one of the films that has had the biggest influence, not only on the movies, but on art, literature and even architecture and design, in history. Despite all this, Fritz Lang himself disowned the film nearly from the day it was released.

Perhaps the best way to tackle all this is to start with the plot. And when I say ”the plot” I mean the plot of the 2010 restored version of the film, which is by no means the original version of the film, but the version that comes closest to Fritz Lang’s original vision. It goes something like this:

In the future city of Metropolis the population is divided into the workers and the owners – although there seems to be something of a gradual curve to these things, and going up and down the prosperity ladder is apparently an option, as the elite has a ruler and also subjects – henchmen, assistants, etc, who are not really workers, but not really elite either. Anyway, the owners live above ground in a splendid, sprawling art deco city filled with neon lights, skyscrapers, slick suspended rail traffic, etc. The sons of the elite wear white sport suits as they engage in healthy gymnastics at oversized Greek-styled stadiums, or frolic in ”The Garden of the Sons”, where they are entertained by a myriad of scantily clad women eager to please with role plays and games. Apparently without doing much work, they can return home to their fathers amid grand luxury.

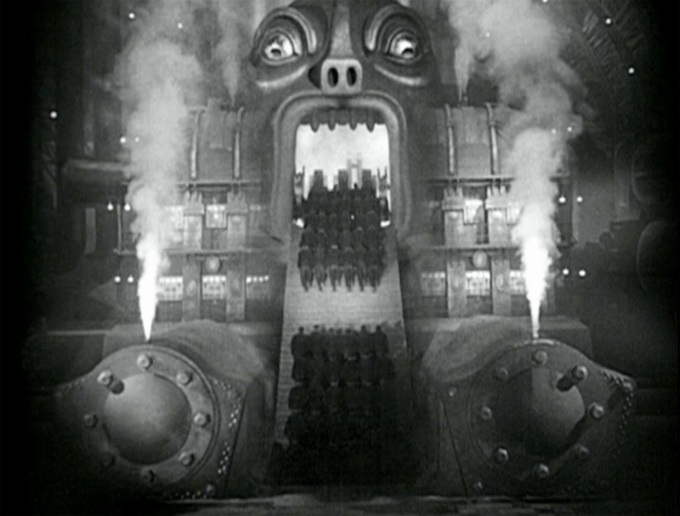

The most pampered of all the sons is Freder Fredersen (journalist-turned-actor Gustav Fröhlig), son to the creator and ruler of Metropolis, the ruthless Joh Fredersen (seasoned actor Alfred Abel). But one day during his merrymaking in the Garden, the angel-faced Maria (a 19 year old Brigitte Helm in her first film role) turns up with a host of dirty children in rags. ”Freder Fredersen”, she demands, ”look at the children of those who are your brothers”. Then she is quickly ushered away. The interest of Freder is piqued, though, and he later follows her trail down to the underworld of Metropolis, known as the Workers’ City. Far beneath the ground is another city, inhabited by the workers, whose lives consist purely of routines demanded by the 10-hour clock devised for them by Fredersen to increase effectivity. Like the machines they handle, the workers walk like robots in straight lines on and off duty by the minute, working gruelling hours with monotonous, physical and dangerous labours. One of the worst jobs is apparently one where a worker has to manoeuvre the dials of what looks like a giant clock to match blinking lights. As Freder watches, the worker doing this shift collapses. Freder, appalled by what he sees, offers not only to pick up the rest of the shift, but to change lives with the worker for a week. Thus he continues the horrendous routine, later replicated in hilarious fashion by Charlie Chaplin in Modern Times. While at work he hallucinates from the sheer horror of it all, seeing the great stairs of the factory as a grotesque demon’s mouth, devouring its slaves, and witnesses an accident which takes the lives of several workers, without anyone seeming to care. When confronting his father with this, his father is mostly angered that his assistant Josaphat (Theodor Loos) has not told him about the accident earlier. The workers’ foreman Grot (Heinrich George) informs Joh that yet another set of mysterious maps have been found on the bodies of the dead workers. Josaphat is fired by Joh, and is ready to take his own life at this dismissal, when Freder offers to hire him as his assistant. Freder is now determined to delve deeper into the mysteries of how Metropolis is actually run. Joh is alarmed by Freder’s unusual behavior ans despatches his hitman The Thin Man to keep track of him.

Joh visits his old friend, a mad scientist who he is now on uneasy terms with, Rotwang (beautifully played by Rudolf Klein-Rogge in a character-defining role), to find out what the maps mean. It seems they show the catacombs of the old city that Metropolis was built upon, lying beneath the worker’s city. In the process we also learn that Freder’s mother died while giving birth to him, and that she was initally Rotwang’s girlfriend. In his grief Rotwang has created a ”machine human”, a robot, a Maschinenmensch, who he intends to give the features of his beloved woman.

Together they explore the catacombs, and find Maria holding a religious vigil, a saintly figure bathed in light in front of a huge cross and altar, telling the story of Babylon, and how the workers of the city will unite in a struggle, but will find it futile until the mediator can step in and reconcile the rulers and the workers. He must be the heart that brings together the hands (the workers) and the heart (the rulers) of the city.

Rotwang then gets the idea to capture Maria, and give her features to the Maschinenmensch. To Joh he says that she will betray the workers, but secretly he plans to bring down Joh Fredersen and his city. And so he does in a spectacular sequence with elaborate special effects. The fake Maria then takes up a job as an exotic dancer in Metropolis seedy mens’ club, in a dance sequence that would never have passed the American sensors after the infamous Hays Code was enforced in 1934. Lang fills the screen with drooling, lust filled men’s faces, and creates an expressionistic collage of watery eyes watching the woman. Riots break out when horny rich men fight over this new Maria. Below the surface the timid peace-preaching Maria is replaced by a fiery revolutionary that incites a violent uprising and death to the usurpers. ”That is not Maria!” Freder shouts, but is fought off by the angry mob, that then takes to the streets, while Freder goes in search for the kidnapped real Maria, who he finds in the strange, arcaic house that belongs to Rotwang. He ultimately frees her, while the workers move up the surface, where they demand that the machines be destroyed. ”No, are you crazy?” demands Grot, ”the whole worker’s city will be flooded”. But the fake Maria urges them on, and they smash the machinery. Meanwhile the real Maria has now become trapped below, where she discovers that all the workers’ children are also trapped, and the water is now flooding in. She gathers them all in the square, where she sounds the alarm gong, drawing Josaphat and Freder who have come to their rescue.

Learning about the trapped children, the workers turn on the fake Maria, and chase her through the streets, where they have her burned at a stake, and ultimately it leads to a dramatic showdown between Freder and Rotwang at the roof of a cathedral. Rotwang is killed, but seeing his son in mortal peril, Joh Fredersen realises his folly. With Maria’s help, Freder then becomes the mediator (the heart) between Joh Fredersen and Grot, resulting in a diplomatic handshake and a promise of co-operation.

Whoah. This was the longest plot summary I have written so far, and I have left out the spectacular scenes with Freder and Death in the cathedral, the whole subplot with the worker who trades lives with Freder, and Josaphat’s fight with The Thin Man, as well as the illness and hallucinations of Freder. But it is all necessary, since every single scene in this film is so iconic – whole films have been inspired by single scenes in Metropolis.

********************************************************************************************

THE SHORT-SHORT PLOT SYNOPSIS: In the future city of Metropolis, the workers are treated as machine-like slaves by ruler Joh Fredersen (Albert Abel). His son Freder (Gustav Fröhlig) joins forces with the workers, led by spiritual leader Maria (Brigitte Helm). The mad scientist Rotwang (Rudolf Klein-Rogge) creates a robot copy of Maria (who he kidnaps), that tries to destroy both the workers and the rulers, bringing an end to Metropolis. In the end Freder saves both Maria and the day by becoming the mediator that Maria has foreseen, and becomes be the heart that brings together the hands (workers) and heads (rulers) of the city in understanding and co-operation.

********************************************************************************************

Where does all this start then? It starts with Fritz Lang and his wife, author Thea von Harbou. Harbou wrote a novel with the sole purpose of turning it into a film, and worked out the screenplay with Lang. Several plotlines and themes were dropped from the book, such as the ones concerning magic and occultism (although hints of it remains, as in the strange house of Rotwang and the largely unexplained transformation of the C-3PO-like robot into Brigitte Helm). The script went through several changes – in one version Freder flew to the stars, but this ultimately became he premise of Lang’s 1929 film Woman in the Moon (review). Harbou’s novel was itself inspired by H.G. Wells – most notably The Time Machine, with its depictions of the Morlocks ans Eloi, as well as The Shape of Things to Come, and other more political works, and Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, along with several German dramas and the biblical story of the tower of Babylon.

Fritz Lang was one of Germany’s most celebrated directors at the time, having created the popular adventure films Die Spinnen I and II (The Spiders, 1919-1920), the horror film Destiny (Der Müde Tod, 1921), the heralded Dr Mabuse, the Gambler (1922) and the hugely popular five hour epic Die Nibelungen (1924). With Metropolis the film company UFA gave him completely free reins and a more or less unlimited budget, which basically bankrupted the company.

It is unclear whether Lang and Harbou were inspired by the Soviet sci-fi epic Aelita (1924, review), but there are certainly many similarities, such as the underground slave workers, the female revolutionary leader that turns on her flock, the ruthless dictator, the ambivalence concerning popular uprisings and not least the futuristic/alien design. Neither Lang nor Harbou ever cited Aelita as an influence, and it is conceivable that they both simply picked up on themes and styles that were popular at the time.

The impressive art deco sets were the largest built in Germany at the time, incorporating gigantic buildings and whole city blocks, big, moving elevators, stadiums, gardens and a large square that was completely flooded. The miniature work was some of the best, if not the best, that had been put on screen at this time. Each and every frame of the film was meticulously worked out by Lang, and he was exacting to a degree as how they were to be filmed, often without regard for how many retakes it required. The actors involved unanimously described the experience as a nightmare. Best known is the scene where Lang had Brigitte Helm and hundreds of poor children standing for days on end in water that he deliberately kept at a low temperature. He insisted on using real fire for the burning of the fake Maria at the stake – causing Helm’s helms to catch fire. A simple shot of Freder collapsing at Maria’s feet took two days to film, and Fröhlig was reportedly completely drained afterwards. This was the film when Lang ultimately established himself as a demon director caring little for the comfort of his actors. One commentator has described Stanley Kubrick as a teddybear compared to Lang. Whatever the human cost, the end result is staggering. As mentioned before, each and every scene of the film is absolutely iconic, stunning – from the hand held cameras used in the catacomb chase scene, to the science fiction classic of Maschinenmensch coming to life, to the mechanical routines of the workers or the impressive mass scenes that are featured in abundance. Every single shot is perfectly framed, lit, constructed and choreographed. And the plithe of the actors definitely turn into realistic performances. The special effects were groundbreaking. Special effects expert Eugen Schüfftan came up with a new method of shooting miniatures with a camera on a swing, later labelled the Schüfftan process. An ingenious way of filming through mirrors made it possible to place live actors inside miniatures, a process that demanded a huge amount of detailed work. The robot, the Maschinenmensch, was built around a full body cast of Brigitte Helm, and the influential suit was sculpted by Walter Schulze-Mittendorff, thus defining for all times what an android looks like.

Metropolis has a four-clover of lead actors. Lang decided to pitch two German veterans against two almost completely unknown youngsters. Alfred Abel and Rudolf Klein-Rogge were already familiar faces for Lang. The former appeared in Destiny, and the latter in Destiny, Dr. Mabuse, the Gambler, as well as in Die Nibelungen. The title role as Mabuse had catapulted Klein-Rogge into great fame, and he would later reprise the role in the internationally acclaimed talkie The Testament of Dr. Mabuse (1933). (Trivia: Klein-Rogge appeared in an uncredited bit part in the 1919 expressionist horror masterpiece The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari.) Abel is able (pardon the pun) as the cold-hearted Joh Fredersen, who softens to the sight of his son in mortal danger, although he is not really given the chance to shine. Klein-Rogge, having already set the template for the world-dominating supervillain with Dr Mabuse, here firmly establishes the blueprint for yet another movie staple – the mad scientist. Here he is with a white lab coat, white hair on end, goggles on forehead, a mechanical hand, waving and snarling, going off on crazy rants, while fiddling with his buttons and levers. Although several films had toyed with the mad scientist theme before, like the 1910 Frankenstein and the many Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde films, this is the first one where the stereotypical, full-blown mad scientist really springs into action. Gustav Fröhlig was a fairly unknown actor, actually a journalist, who in 1922 also started appering in smaller parts in films. He certainly holds his own against the veterans Abel and Klein-Rogge, not only putting in a heartfelt performance, but an impressive load of physical work. The real icon of the movie is, of course, the legendary femme fatale Brigitte Helm, who was only 18 when filming began, and whose only film experience was a screen test for Die Nibelungen. Helm is a natural, effectively juxtaposing the timid, soft and chaste beauty of the saintly Maria, and the twitching, diabolical, sexual evilness of the fake

Maria/Maschinenmensch. The famous dance scene with the fake Maria wearing nothing but a loincloth and some glitter to cover her nipples probably had many males in the audience gasping for breath just as much as the young men of Metropolis. Helm takes absolute control of almost every scene she appears in, and with such bravado that it is very hard to believe that it is only her first film. After this she was typecast as a vamp, and twice had to play the role of the man eating soulless Alraune, both in the 1928 silent version (review) and the 1930 talkie. After Metropolis she got a 10 year contract with UFA, and more or less had to play whatever they placed her in, and in 1929 she took UFA to court when she tried to get out of playing vamps, but lost, and most of her salary after that went to paying off the court debts. Her 29 films was a rollercoaster of bad and brilliant movies – notable are The Love of Jeanne Ney (1927), where she plays a blind woman, Crisis (1928), where she portraits a spoilt woman of the world who from sheer boredom almost destroys her own life, and L’Atlantide, where she plays a an opaque, otherworldly goddess driving men crazy. She was considered for the title role of James Whale’s masterpiece Bride of Frankenstein (1935, review) before Elsa Lanchester was cast. Before she quit acting she appeared in yet another sci-fi film, the today largely forgotten classic Gold (1934, review), where she got to play an unusually well-balanced character. Helm also led a much publicised private life. In 1935, when she made her last film, she enraged the Nazis by marrying an Jew. She was also a reckless car driver and was involved in several car accidents, one with a fatal outcome, for which she served a short sentence. But such was her fame, that Adolf Hitler himself is said to have seen to it that she got pardoned. After 1935 she completely withdrew from films and public life, and almost never gave any interviews. In the sixties she was tracked down by a journalist, but wouldn’t let him inside the house. In the end of the eighties she gave an interview, but on the premise that it was only going to be about fashion. Nevertheless, she is fondly remembered as a true icon of cinema.

Much like its Soviet counterpart Aelita, Metropolis has intertwining plotlines and characters that we sometimes lose for great chunks of the film. Unlike the former, these subplots never distract from the main plot, and always have a connection with the overall arc. The film doesn’t get boring for one minute, rather one dramatic and visual grand piece follows the other. But also unlike Aelita, this film offers no subtle and intelligent musings on contemporary society. Where Aelita used tiny and subtle chisels to carve out biting satire of the Russian revolutionary pathos, Metropolis goes at its political statements with a sledgehammer. The conclusion with the workers and rulers shaking hands in a ”why can’t we all be friends” moment is nothing short of naive, although heartfelt. Fritz Lang later disowned the film, saying the political statement was ridiculous. ”I wasn’t thinking very politically back then”, he said in an interview, ”of course you can’t make a political movie and say that the mediator between the head and the hand must be the heart”. It has been considered that one of the reasons Lang later came to dislike the film was that it was so embraced by the Nazis. Lang himself fled to the States where he continued his illustrious career, after divorcing his wife, writer Thea von Harbou when she became a devoted Nazi.

Fritz Lang is one of the true greats not only of German, but international cinema. After establishing the pre-Blofelt world dominating villain with Dr. Mabuse, and revolutionised sci-fi with Metropolis, he made the expressionist spy classic Spies (1928), and created the template for all other moon travel films with Woman in the Moon (1929), where he was the first to introduce the countdown for take-off, the first to depict a scientifically correct moon rocket and the first to tackle weightlessness on a spaceship. He also created a liftoff area and scaffolding eerily similar to the later real-life takeoff areas in America. The 1931 expressionist masterpiece, and Lang’s first sound picture, M, is considered one of the greatest films of all time, and a huge influence of the film noir genre. Before fleeing to USA, he still had time to make The Testament of Dr. Mabuse in Germany in 1933. He made over 20 films in the States, many of which are today considered highly influential classics, such as Fury (1936), the epic western Western Union (in colour, 1941), the Bertolt Brecht-scripted Hangmen also Die! (Venice film festival winner, 1943), The Woman in the Window (1944), a film that among a few others marked the onslaught of American film noirs, the violent, dark The Big Heat (1953), noted for the brutal disfigurement of star Gloria Grahame, after Lee Marvin’s thug throws scalding coffee in her face, and the geometric, cold noir While the City Sleeps (1956). Few directors have had such a huge influence on so many genres, and had such a productive and creatively successful career over so many decades. The great shame is that he was not always as revered during his American years as he should have been, and that he never won an Oscar, not until 1976, when he got a lifetime achievement award just six months before his death.

Picking the best Fritz Lang film is like picking the best composition by Mozart. How can you choose just one? Metropolis, though, is probably the one that is best known to the general audience, although films like M, The Woman in the Moon and The Big Heat may have been just as influential on the medium of film. It is tempting to remove one star for the muddled and naive political message, and the pompously dramatic religious parallels, but another one should be added for the astounding impact it had on film, art and style in general. And, hey, if you can’t give ten stars to Metropolis, which sci-fi film can you give it to?

The original release of the film was 153 minutes long – considered too long by the American distrubutor, who slashed it down to 115 minutes. This resulted in some audiences feeling confused by characters appering without any introduction, unclear character motivations, and and overall feeling of a jumbled script. It was further slashed in 1936 almost to an unrecognisable form of 91 minutes in America, removing all communist subtext and religious imagery – this was in the early days of the infamous Hays Code. The original print was lost, and thus the 91 minute version was the only commercially available one for decades, until Italian musician and film buff Giorgio Moroder made a serious attempt at restoring it from different versions – and unfortunately he also added a much derided pop soundtrack. This version, however, re-ignited the interest in the film, and museums and archives around the world started unearthing previously unknown clips of the film, resulting in a 118 minute version being released by the F.W. Murnau Foundation and Kino International in 2002. In 2008, by some miracle, an almost intact copy of the original edit was discovered by a film museum in Argentina. Around the same time another version with previously unseen material was discovered in New Zealand, and another one in Australia, apparently all shipped out in 1928, before the international distributor in America started chopping the film. This resulted in an almost complete version being released in 2010, running 148 minutes in length, that substituted the lost footage with explanatory title cards.

The film has a whopping 99% Fresh rating at Rotten Tomatoes, was named as the 12th best film not made in English of all times by Empire Magzine in 2010 (Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai was number 1) and the second best silent film on the list (beaten by Sergei Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin). The British Film Institute has named it as the 35th greatest film ever made.

Metropolis was the first real sci-fi epic made at a grand scale, not counting Aelita. At 5 million Reichsmarks it was the most expensive film ever made when it was released. Its art deco view of the future is thought to have been a big reason as to why the style became so hugely popular in architecture and interior design in the late twenties and early thirties. Its sprawling skyscrapers (inspired by Lang’s first visit to New York) and suspended roads and tracks formed the vision of the future city for decades to come – a vision that still lives on today. Great homage was paid to Otto Hunte’s Erich Kettelhut’s and Karl Vollbrechts design team in Ridley Scott’s masterpiece Blade Runner, almost replicating in detail certain shots, buildings and vistas of the film – most notably one of the circular towers, and the flickering advertisements on the sides of the skyscrapers. The

Maschinenmensch, designed by Walter Schulze-Mittendorff, and played with much discomfort by Brigitte Helm, forever set the standard for what an android looks like, and it was replicated as C-3PO by George Lucas in Star Wars. Too much praise cannot be heaped upon the master cinematographer Karl Freund and his team, combining huge wide shots with narrow, shaky camera movements, impressive pans, moving cameras, skewed angles, intimate close-ups and remarkable framing. Freund later went on to bring expressionist horror to Hollywood with Dracula (1931) and The Mummy (which he directed, 1932), who won two Oscars, and was considered one of the true technical (one of his Oscars was for inventing a new light meter) and artistic innovators of American cinema. Fritz Rasp as The Thin Man would go on to portray the evil American spy “The man who calls himself Walter Turner in Lang’s Woman in the Moon (1929).

Janne Wass

Metropolis. 1927, Germany. Directed by Fritz Lang. Written by Thea von Harbou, Fritz Lang. Starring: Brigitte Helm, Gustav Fröhlig, Alfred Abel, Rudolf Klein-Rogge, Fritz Rasp, Theodor Loos, Henrich George, Erwin Biswanger. Cinematography: Karl Freund, Günther Rittau, Walter Ruttmann. Art direction: Otto Hunte, Erich Kettelhut, Karl Vollbrecht. Special effects: Ernst Kunstmann. Visual effects: Eugen Schüfftan. Produced by Erich Pommer for UFA.

Your sentence regarding the role of the mediator mentions “heart” twice, and I think the second reference should have been “head.”

LikeLike

Thanks, you’re probably right. 🙂

LikeLike