∗∗∗∗∗∗∗∗∗∗

(9/10) In a nutshell: Perhaps the best sci-fi film of the fifties, this 1951 movie directed by Oscar winner Robert Wise took a risky move by presenting a leftist peace statement just when the McCarthyist blacklistings were clamping down on Hollywood. Hugely influential on sci-fi tropes, it is remembered for its sleekly designed flying saucer and the menacing robot Gort, as well as for its realistic direction and impressive special effects, and for cementing the theremin as the sci-fi composer’s instrument of choice.

The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951). Directed by Robert Wise. Written by Edmund H. North. Based on novella Farewell to the Master by Harry Bates. Starring: Michael Rennie, Patricia Neal, Hugh Marlowe, Sam Jaffe, Billy Gray, Lock Martin, Richard Carlson, David McMahon. Tomatometer: 94 %. IMDb score: 7.8

Along with George Pal’s Destination Moon (1950, review) and Howard Hawks’ The Thing from Another World (1951, review), Robert Wise’s The Day the Earth Stood Still would set the template for science fiction films for a decade to come. Two years in the making, this was the second bone fide A-list sci-fi film in Hollywood, after The Thing (Destination Moon’s budget of 600 000 dollars could be described as an unusually big B movie budget). The money shows, both in the fact that the filmmakers have had time for generous pre-production, and in the talent, the sets and the special effects.

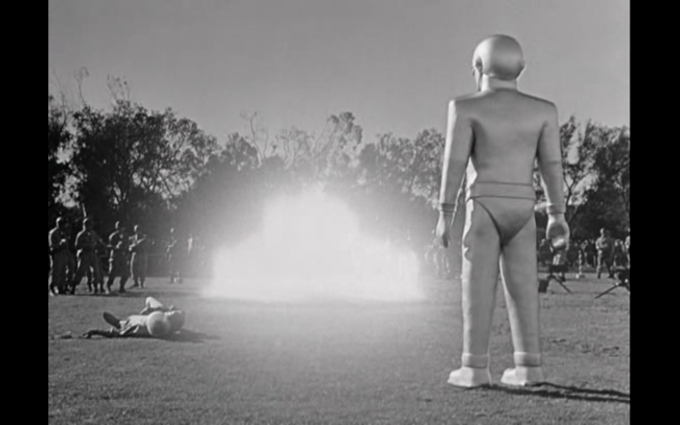

It feels almost silly to recap the plot, since I’m sure everyone reading this blog will be familiar with it, but for the sake of form, the short version is this: A UFO lands in a stadium in Washington D.C, setting the media alight with speculation on whether this is the end of the world or simply some new Soviet trick. The hubcap-shaped spacecraft carries two passengers, spaceman Klaatu (Michael Rennie) and his big robot guardian Gort (Lock Martin). In the face of a couple of army battallions, Klaatu professes to come in peace, but is nonetheless shot by a nervous soldier. Gort fires off a ray from the eye-slit in his ominous helmet, melting away weapons and tanks, until Klaatu commands him to stop, and is then taken to a hospital, where he makes a miraculous recuperation thanks to some super-medicin he brought with him.

Klaatu tells the US president’s secretary Mr. Harley (Frank Conroy) that he wishes to meet with all the leaders of the world to bring a message important for the survival of the Earth. Mr. Harley politely informs him that during current political situations this will hardly be possible, and after failed attempts at this, Klaatu sneaks out from his hospital prison to try and find out more about this world that he has arrived to, stealing the clothes and briefcase of a Mr. John Carpenter, a name which he promptly assumes. He takes up lodging with the family of Helen Benson (Patricia Neal) and her son Bobby (Billy Gray). With Bobby as a guide he learns about humanity and their great thinkers (that is: the founding fathers and Abraham Lincoln, a pretty dry selection if you ask me), and grows fond of both him and Helen.

When asked who the smartest man on the planet is, Bobby answers that it must be Professor Jacob Barnhardt (Sam Jaffe), whom Klaatu seeks out and reveals himself. Since Klaatu can’t get all the world leaders together, he charges Barnhardt to summon a meeting of all the great scientific minds of the world by the spaceship, and promises to give them a demonstration which will cause the world to listen. This demonstration turns out to be disabling all electricity for half an hour, making the Earth, in effect, stand still. But alas, Helen’s obnoxious, nosy fiancée Tom (Hugh Marlowe), suspects a rat, just as Helen and Bobby have just learned who Klaatu really is, and calls the hounds on him, and he Klaatu shot dead in the street. This activates the hitherto immobile Gort, who takes out the flimsy guard duty at the space ship and advances on Helen, who has come to deliver the magical words ”Klaatu barada nikto”, which Klaatu has taught her as a password. She faints, and Gort carries her into the spaceship, and then leaves to get Klaatu. Back on the ship, Helen watches as Gort resurrects Klaatu in a strange machine. He tells her that it is just temporary resurrection since ”only the almighty spirit” can restore life. Just then the army, police and the scientists have gathered around the UFO, and Klaatu exits to give his speech. Essentially, he tells all gathered that they must stop squabbling among themselves. Long have the aliens watched the human wars and let them be, but after the creation of the atom bomb, they feel it is only a matter of time before Earth’s wars extend into space. Klaatu explains that the Universe has achieved peace though creating a peace-keeping force made up of robots such as Gort, which obey no masters, and cannot be turned off. These robots have the power to destroy worlds, and will do so if any of them threatens the intergalactic peace. Such will also be Earth’s fate unless we learn to live in peace and harmony. Then he enters the spaceship again, and leaves for the darkness of the night sky.

As most reviews point out, the film is ”based” on Harry Bates’ short story Farewell to the Master, originally published in the pulp magazine Astounding Science Fiction in 1940. However few reviewers seem to have actually read the story, since some of them even call the film ”a literal adaptation”. But the film is only based on the short story to the extent that Temple of Doom is a film about archaeology. Anyone reading the story expecting the adventures of Klaatu in Washington, the Earth standing still, a biblical metaphor or a message of peace will be deeply disappointed.

The whole thing came about when producer Julian Blaustein at Twentieth Century-Fox was looking around himself at the cold war, McCarthyism, the fear of the atom bomb and the whole crazy world – and figured that he wanted to make a film about peace, international cooperation and good will towards men, at the same time warning against fearing the Other, and reacting to fear with prejudice, hatred and violence. On a more practical side, he was a strong believer in giving the newly founded United Nations a stronger mandate to act as world police. But he knew this was not a story he could tell straight out, but needed a metaphorical vehicle. He had noticed the growing sales of adult science fiction magazines (this was still 1949, before sci-fi had reached the big screen) and thought that science fiction would be a perfect medium to tackle a serious and heavy theme, and let it slip past the right-wing McCarthyist cencors in the guise of a fairy-tale. So he set out finding a story he could build a script on. After reading over 200 stories and novels, an aide brought him Farewell to the Master. Blaustein didn’t think it was a particularly good story in and of itself, but it had an image that resonated strongly: the image of Klaatu holding up his hand in greeting, and subsequently being shot to death because he represented something people didn’t understand, and thus feared.

The story is set in the not too distant future, when humans have already travelled to Mars and to the sun (accidentally, unfortunately). It opens in medias res and follows a photo journalist called Cliff, who tries to unravel the mystery of a spaceship that suddenly appeared outside the Smithsonian Institute in Washington. Much of the story is told in flashback: Cliff and a voice on the museum speaker tell of the spaceship and what happened when it finally opened after two days of terrified waiting. A man came out, followed by a huge robot, built to perfectly match human anatomy, muscles and all, but made out of an unknown greenish metal. The man raised his voice in courteous greeting and said in English: ”I am Klaatu, and this is Gnut”, and was then immediately shot dead by a deranged man who thought the world was going to end. Gnut assumed an immobile position outside the spaceship, and Klaatu was buried by the authorities, and then nothing happened for days and weeks and months. Gnut was thought to be immobile, perhaps turned off, and was impervious to all weapons or tools of man, and could not be budged. But Cliff, after taking a number of pictures every day, started noticing small changes, as if Gnut would have moved during the night when he was only guarded by the Smithsonian’s own crude robots.

Thus begins the story of reporter Cliff and Gnut, the giant robot, and their unlikely friendship, as Cliff sneaks into the museum several nights to watch Gnut go in and out of the spaceship. He sees Earth animals exit the spaceship and die, he gets caught by Gnut, who doesn’t harm him, but instead saves him from a rampaging gorilla. Finally Cliff is invited into the spaceship, where he meets a copy of Klaatu. Klaatu tells Cliff that Gnut has made this copy by reverse-engineering him from the short voice recording broadcast through the speakers of the museum every day, of his first introductory greeting. But since the recording had imperfections, so did the copy of Klaatu, and the copies kept dying within a few minutes. But the Klaatu copy is benign and holds no ill will, and is impatient to be resurrected as a better copy to learn more about Earth.

Cliff says he can get the original recording from the record, which contains less imperfections, so that Gnut might make a longer-lasting copy, a Klaatu as good as the original, perhaps. Klaatu embraces the idea and then dies. Before leaving the spaceship, Cliff asks Gnut to tell the next copy that the killing of Klaatu, Gnut’s master, was a mistake and not meant as a hostility, to which Gnut answers: ”I have already understood”. But Cliff again implores Gnut to tell this to his master also. Gnut answers: ”You misunderstand. I am the master.” And with those words, the story ends. You can find a transcript of the story online, and if you don’t want to read through it all, here’s a fairly representative comic version written by Marvel editor Roy Thomas in 1973.

The Day the Earth Stood Still is often credited as pioneering the idea of the benign alien, as if all depictions on screen up until that time had been of evil aliens, but this is not entirely accurate. It is true that much of the alien encounters (to the small extent that they existed) in film serials and TV shows had been with aliens intent on destruction and invasion. But a story very similar to the film had already seen the light of day in Germany, with Der Herr vom Andern Stern (1949, review). Flash Gordon (1936, review), and it’s many copies, were filled with both benign and evil aliens. And what was Superman, if not the friendliest alien the Earth had ever seen? In The Man from Planet X (1951, review), the alien was initially friendly, but provoked by humans. A similar story played out in the 1951 film Superman and the Mole-Men (review). Even if the Mole-Men weren’t aliens per se, they served the same story purpose.

Bates’ short story wasn’t the first one to promote friendly aliens in literature, either. J-H Rosny Ainé, Camille Flammarion, Edgar Rice Burroughs, Stanley Weinbaum and many others had written about benign aliens long before 1940, and before Blaustein picked up Farewell to the Master it was a fairly obscure tale. The film, however, did have a resounding impact. Even if the fifties red-scare mentality was more fruitful for scary aliens, The Day the Earth Stood Still came to impress many future filmmakers, and inspired movies like The Planet of the Apes (1968), Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977) and E.T. (1982) with its view on the meeting of different cultures.

So, Blaustein had his story and now had to persuade studio boss Darryl F. Zanuck to produce a left-wing, liberal, pacifist film about peaceful cooperation in the midst of the on-going war with Korea, and the blacklistings of McCarthy’s committee. After some deliberation, Zanuck is quoted as saying ”To hell with it! Let’s go ahead anyway. It’s a good piece of entertainment. I believe in it.” Fox staff writer Edmund H. North wrote the screenplay, added all of Blaustein’s ideas on peace and an intergalactic police force, the titular stunt of stopping the world, basically invented all the characters, including Klaatu, who really wasn’t much of a personality in the story, and removed the main character from the novella. What remained from the original story was the atmosphere of fear and confusion surrounding the alien, the peaceful intent of the visitors, Klaatu and Gnut (who became Gort), and the spaceship. Klaatu’s death was included, as it was the central point for Blaustein. However, North didn’t have Gort making copies, but actually resurrecting Klaatu – for good. But the censors took offense to this, and saw it as blasphemy, as only god could resurrect people, in their opinion. Therefore, they wanted North to rewrite the plot so that Klaatu was only temporarily resurrected, and he even had to include the line about ”the almighty spirit”, which stands out like a sore thumb in the film.

Today the Christian allegory is well documented. Klaatu descends from the heavens with magical powers, benign intent and wisdom, dies for humanity, is resurrected to deliver a sermon and then ascends to the heavens again. North even gave him the alias John Carpenter, which shares initials with another J.C, who also happened to be a carpenter. North never spoke of this allegory with either Blaustein or the director Robert Wise, as he hoped it would be ”subtle”. Indeed, Wise later said that he never thought of it during the making of the film, but to be honest it is just as ”subtle” as the rest of the ”sub”context in the movie. North received an Oscar for his script for Patton in 1970, and wrote the sci-fi film Meteor in 1979.

Director Robert Wise was Blaustein’s first choice, as Blaustein was impressed with his previous dozen films, including the film noir The Curse of the Cat People (1944), the horror film The Body Snatcher (1945) and the crime noir The House on Telegraph Hill (1951). Wise also shared Blaustein’s ideological views, although he wasn’t quite as outspoken about them. He had previously worked as a sound editor and later film editor for greats such as John Ford, William Dieterle and Orson Welles, for whom he edited Citizen Kane, which gave him an Oscar nomination, and he re-edited the infamous The Magnificent Ambersons, which earned him many years of grudge from Welles.

Perhaps inspired by Welles, Wise wanted to ground the fantastical story in reality by shooting in black and white and giving the film a documentary style. Although most of the film was shot in Fox studios and backlots, he wanted real footage of Washington, and sent a second unit directed by Bert Leeds there to get blocking shots and background shots for scenes at the Washington memorial, Capitol Hill and the graveyard of the unknown soldiers, as well as ordinary Washington streets. The shots of the Earth standing still are also partly shot on the streets of Washington. Wise also included a number of famous news broadcasters to deliver news on the UFO landing and newspapers and radio broadcasts help to tell parts of the exposition.

Also inspired by directors like Dieterle and Welles, Wise employs a lot of night shots, shadows and expressionistic lighting familiar from film noirs, like in the effective scene where the family first encounters ”Carpenter”, an ominous figure hidden in shadows, standing in the doorway – and then turns it all around by having the gentle, smiling Rennie step into the light, asking for lodging. Overall the direction is superb, and one especially admires the flawless rear projection filming and blocking of Klaatu and Bobby visiting Washington landmarks. Wise have them walking inside the Washington monument without the actors ever having been there, and I still don’t know how he pulled it off.

Robert Wise was one of the most versatile directors in Hollywood, effortlessly leaping from genre to genre. He did westerns, noirs, horror films like The Body Snatcher and The Haunting (1970), historical dramas and war films, as well as extravagant musicals like West Side Story (1961) and The Sound of Music (1965) – both films earned him Oscars for best film and best direction. He made the backstabbing business drama Executive Suite in 1954 and the gripping courtroom drama I Want to Live! in 1958, about a prostitute wrongfully accused for murder. In addition to The Day the Earth Stood Still, he made another visionary science fiction film in 1971: The Andromeda Strain, and after the success of Star Wars, he was enlisted to direct Star Trek: The Motion Picture in 1979, which rebooted the cult series from a decade earlier.

The question of casting brought Fox some headaches. The studio wanted to cast a well-known star as Klaatu, and a serious pitch was made to Blaustein for Claude Rains, who turned out to be unavailable. Blaustein instead wanted an unknown actor, since a Hollywood star would give away the illusion of him actually being a visitor from another planet. Still, Richard Zanuck sent the script to Spencer Tracy, at the height of his career, and Tracy even agreed to do the movie. Blaustein pleaded with Zanuck and managed to get Tracy off the film. Instead he opted for British theatre actor Michael Rennie, who was a minor film star in Britain, but still largely unknown to an American audience, as he had only done two films for Fox the previous year.

Rennie is the heart of The Day the Earth Stood Still, playing the sympathetic, but enigmatic Klaatu with wits, warmth and charm. Especially memorable are the scenes Bobby and Klaatu together, in what seems like completely effortless acting from both of them. What makes his performance great is partly that he isn’t classic leading man material – though tall and handsome, he lacks that imposing quality that many leading men actors have, making them dominate every scene they’re in. Instead, Rennie glides through the movie, creating a believable illusion of the sometimes bewildered alien passing perfectly as any man on the street. Nonetheless, he has all the acting chops of many of his more famous heroic colleauges, if not more, and is able to appear thoroughly stern and even threatening when called upon to do so.

After the success of the film, Fox briefly tried to pin him as a leading man, but instead he had a successful career as a supporting character actor, although he is probably best remembered, after The Day the Earth Stood Still, as the leading man in the TV series The Third Man, which ran from 1959 to 1960. He avoided typecasting in science fiction films, and didn’t make his next sci-fi until 1960, when he appeared as Lord John Roxton in Irwin Allen’s version of Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Lost World, infamous for its slow-motion lizards with glued-on horns standing in for dinosaurs. The sixties saw him making more sci-fi, possibly because his career was going slightly downhill, and he appeared in Cyborg 2087 (1966), in the lead as the cyborg from the future, George Pal’s The Power (1968) and the Spanish Assignment Terror (Los monstruos del terror) in 1970, again in the lead, as Dr. Odo Warnoff. This was his last film. He also appeared in a number of sci-fi series, perhaps best known as the villain The Sandman in Batman in 1966.

Helen’s role is unusually well written for a fifties sci-fi film, and she is portrayed as a smart, caring, funny and stubborn woman, the first person to suspect that little Bobby might be right when he says Mr. Carpenter is the spaceman. Patricia Neal plays her very naturally, except for the one scene when she is confronted by Gort and in fear screams and throws herself face down on a pile of folded chairs. Because that is what we all do when in deadly peril – we throw ourselves flat on the closest uncomfortable and potentially harmful object we can find. But it is in the moment after that she utters those famous words: ”Gort! Klaatu barada nikto!” Despite ”alien linguistics editors” trying to decipher the meanings of the words, screenwriter North said he just made them up because ”it sounded good”. Nevertheless, they are some of the most famous words spoken by an extraterrestrial on film (probably outdone by ”E.T phone home” in 1982).

The movie also gave birth to he trope ”We come in peace”, although the actual line uttered by Klaatu is ”We have come to visit you in peace and good will”. In all actuality, I can’t find any films that actually used the ”We come in peace” phrase before the Ethan Hawke vehicle Explorers, made in 1985, and in that film it was the human space explorers who used it. The first reference to the exact phrase used by an alien is in Dolph Lundgren’s Dark Angel, spoken by an alien just before it starts sucking in human brains. In effect The Day the Earth Stood Still also was the first film to use the ”Take me to your leader” trope, although the phrase itself is never uttered as such. The phrases had probably been used in pulp stories and comic books before, though.

Patricia Neal was a Tony-awarded stage actress who had just been laid off from Warner by 1950. In interviews she has revealed that she didn’t think much of the film at the time, and kept ruining the takes because she was laughing so hard over the silliness of it all during filming. She did think it was a good film when she saw it, though. Neal’s film career didn’t take off, as she kept being miscast as clichéd characters like romantic leads, comic frills and femme fatales, none of which suited her more serious talents. It wasn’t until she was cast as he worn-down housekeeper in Hud (1963) opposite Paul Newman that she became a real A-list star – helped by the Oscar award the role gave her. She had previously made lauded appearances, though, in films like A Face in the Crowd (1957) and Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1961). Her one other science fiction film was a blatant British ripoff of The Day the Earth Stood Still, called Stranger from Venus (1954, review).

Neal suffered a loss of one child and the brain damage of another, and herself suffered three near-fatal strokes in the mid-sixties, which left her in a coma – when she woke up she had lost much of her ability to speak and move. She was rehabilitated much thanks to the stubbornness of her husband, famous author Roald Dahl. Her comeback role in The Subject Was Roses (1968) earned her another Oscar nomination. She continued working in film and TV through the seventies, up until her death in 2010. She won a Golden Globe, two BAFTA:s and was nominated for three Emmys in her career.

Billy Gray who played Bobby had been working as a child actor since 1945 and was actually 13 years old, when he was supposed to play a ten-year-old. He does seem a little older than his character in the film, and some of his remarks seem out of place for a boy of his age. On the other hand, the casting of a slightly older boy gets rid of some of the annoying qualities often found in young child actors. Gray is perhaps best known for his recurring role in the sitcom Father Knows Best in the fifties, which earned him an Oscar nomination. Gray has some of the key moments in the film, and is able to pull off a few very good dramatic moments. Especially his scenes with Michael Rennie are good. His only other sci-fi role was the abysmal The Navy vs. the Night Monsters (1966). He was one of the few child actors who was able to transition into adult roles, although work dwindled in the mid-seventies. In 1998 he settled a lawsuit with film historian Leonard Maltin, who in all his film guides from 1974 to 1998 had identified Gray as a real-life drug addict in the film Dusty and Sweets McGee (1971).

The one part that feels strained is Helen’s boyfriend Tom Stevens, as he is there solely to be the annoying, fear-mongering stuck-up who gets Klaatu killed. True, the film needed the character for the sake of moving the plot along, but that doesn’t mean it couldn’t have been better written. Hugh Marlowe was a radio and stage actor who usually played second leads or supporting characters in movies. He did, however, snatch the lead in two other fifties sci-fi films in 1956: World Without End, and the other seminal flying saucer film, Earth vs. the Flying Saucers, known for Ray Harryhausen’s brilliant stop-motion animation. Marlowe was able to get steady employment up until the end of the sixties, when he got a starring role in the TV series Another World (non-sci-fi, despite the name), a position he held until his death in 1982.

As we come to the character of Dr. Barnhardt, we come to the very heart of the film. Chosen to play the role was veteran stage and film actor Sam Jaffe. Jaffe, by then an Oscar-winning and highly praised character actor, was producer Blaustein’s first and only choice. The studio had strong objections – in the midst of pre-production, Jaffe got blacklisted as a communist sympathiser. But Blaustein stood his ground and said that he would make the film with Jaffe, or not make it at all.

This wasn’t simply because Jaffe was a good actor, but because his kind features, his diminutive stature and his wild, curly hair lent him a strong family resemblance to the scientist whom the character of Dr. Barnhardt was based on: Albert Einstein. Einstein’s thoughts and ideas run like a thread through the film. From his warnings about the atom bomb to the leftist leaning of the procedures. In 1949, when Blaustein started pre-production, Einstein wrote an essay called Why Socialism? That same year he started planning a peace convention where all the world’s brightest scientific minds could come together to discuss science and world affairs beyond the boundaries of politics and nations – not very different from the meeting demanded by Klaatu in the movie. Even the name Barnhardt has a symmetry with Einstein. The peace convention did come to pass shortly after Einstein’s death as the Pugwash Conferences on Sciences and World Affairs in 1957, following the Russell-Einstein Manifesto. The organisation won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1995 for its work on nuclear disarmament.

Fox studio head Zanuck gave a green light for using Sam Jaffe in the film, much to the relief of Blaustein and Wise. However, Jaffe didn’t make another film for seven years due to the blacklisting. This was absolutely preposterous to Blaustein, as Jaffe was in his opinion ”a moderate republican”. His career took off again after appearing in the blockbuster Ben-Hur in 1959, although he mostly did work as guest star on different TV series. He appeared as Zoltan Zorba in Batman in 1966, as Admiral Richter in an episode of The Bionic Woman (1976), as Dr. Hephaestus in Roger Corman’s Battle Beyond the Stars (1980) and as Father Knickerbocker in Nothing Lasts Forever (1984), one of his final films.

And so we come to the final, and most iconic, of all roles in the movie – Gort, the robot guardian. I remember being sadly disappointed when I first saw the film some years ago – the influential robot everyone were talking about turned out to be a wobbly, tall guy in a ski-jumping suit and a motorcycle helmet. But of course, the film must be seen in the context of the time it was made. Nothing like it had been seen before. In past films robots had either been clunky things made out of plywood boxes and drain-pipes or simply perfect human copies, doing away altogether with the robot design. This sleek, seamless metal shape was something completely new, and probably the most inventive robot design since the Maschinenmensch in Metropolis (1927, review). The idea was so novel that no-one really was able to pull it off better than designer Addison Hehr until Stan Winston and Industrial Light & Magic made T-1000 for Terminator 2: Judgement Day (1992), with the help of CGI and expensive special effects.

In Bates’ novella, Gnut is described as being made out of some greenish metal, and possessing a fully formed human anatomy, he even wears a loincloth to cover up his naughty parts. His height is never given exactly, but the overall impression is that Gnut is considerably taller than a human. On the other hand, Gnut’s fight with a gorilla seems so even-handed in the short story, that he probably isn’t as tall as the 28 feet (8,5 meters) tall Gort in the 2006 remake of the film.

The filmmakers in 1950 set out to find a really tall actor, which back then wasn’t as easy as it is today, as basketball and show wrestling still hadn’t produced the kind of well-known towering personalities we see today. However, someone remembered that the Grauman’s Chinese Theater in Los Angeles had an unusually tall doorman, who had actually appeared in a few films. Lock Martin was reportedly 7’7 or 231 centimeters tall, although Robert Wise later revised that number to 7’1 or 216 centimeters. Despite his towering stature, he was not a physically strong man, and was in actuality rather frail. This meant that he could only stay for about 30 minutes in the foam rubber suit designed by Hehr before he had to take a break. Wise thought he wasn’t tall enough for Gort, so he had Hehr design him platform shoes and a tall headpiece from which he could only see through with utmost difficulty. He had trouble navigating the ramp of the flying saucer and couldn’t pick up Patrica Neal or Michael Rennie. Therefore, the filmmakers either used lightweight dummies for him to pick up hoisted the actors up with wires – visible in some shots. For the shots of Gort standing still, they used a fiberglass replica of the suit, partly to make Gort completely rigid, but partly to spare Martin the trouble of the suit. The helmet, of course, was not mentioned in the story, nor the desintegration ray. The design of the helmet has become iconic, as well as the undulating light behind its visor.

The trouble Martin had with the suit unfortunately lends Gort a rather wobbly gait, which takes away some of his menacing features and even causes some involuntary comedy, which is a drawback of the film. There’s also a problem with the material of the suit, which makes it form a crease at the knee joint when Gort is walking – exactly the same kind of crease you see in ski-jumping suits, which made the connection for me. Wise was aware of the problem, but found no way of solving it.

As to the character of Gort, he is described in the film as part of an interplanetary police force with ultimate authority. His mission is to keep the peace by way of intimidation and fear – in effect the galaxy has been turned into a sort of police state, which is a bit jarring, considering the film’s ultimate message of co-existence and understanding, and has a rather fascist ring to it. The idea, according to Blaustein, was to convey the idea of a strong United Nations that could intervene in military conflicts with military action.

Lock Martin appeared in 11 films before his death in 1959, only 42 years old. He was the mutant carring David to the Martian leader in Invaders from Mars (1953, review), and is thought (although unconfirmed) to have played the Yeti in The Snow Creature (1954, review). Other sources claim that the Yeti was played by Dick Sands of Phantom from Space (1953, review) fame. Martin also filmed a scene as a giant in The Incredible Shrinking Man (1957), but the scene was cut from the final film.

In a small as role Thomas Stevens Jr. we see a cult legend of B science fiction, Richard Carlson. Carlson had appeared in the TV series Lights Out (review), but The Day the Earth Stood Still was his real sci-fi debut. He went on to B movie fame as the leading man in films like The Magnetic Monster (review), The Maze (review), It Came from Outer Space (review) (all 1953) and Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954, review). He was third-billed in Riders to the Stars (review), which he also directed. In the late fifties ans sixties he concentrated on TV, and is best remembered for playing the lead in the McCarthyist FBI/Communist drama I Led 3 Lives. He made a brief return in elder years to sci-fi in The Power (1968) and The Valley of Gwangi (1969).

Bit-part player George Lynn had previously turned up in House of Frankenstein (1944, review), and played in The Werewolf (1956), The Man Who Turned to Stone, I Was a Teenage Frankenstein and The Deadly Mantis (all 1957). David McMahon, here in a small role as an air force sergeant, had the honour of playing both in The Day the Earth Stood Still and the other superb sci-fi film of 1951, The Thing from Another World. He later turned up in The War of the Worlds (1953, review), The Creature Walks Among Us, It Conquered the World (both 1956), The Monster that Challenged the World (1957) and The Deadly Mantis. Comedian Snub Pollard has a cameo as a taxi driver.

Extra Stuart Whitman also turned up as an extra in When Worlds Collide (1951, review), and slowly started working himself up in his career to an Oscar nomination for The Mark in 1961. He played the lead in the hilarious giant bunny movie Night of the Lepus in 1972, as well as in the sci-fi film Deadly Reactor (1989), and appeared in Omega Cop in 1990. He is probably best known to a certain generation as Superman’s adoptive father Jonathan Kent in the TV series Superboy (1988-1992).

Extra Patrick Aherne had a substantial part in Rocketship X-M (1950, review). In a small role we also see Edith Evanson, who played the widow of the murdered scientist in the pseudo-sci-fi film The Jade Mask (1943, review) and might be recognised as the innkeeper from Journey to the Center of the Earth (1959).

The quality of the film is proven by the talent involved: almost all artistic and technical crew on key positions are either Oscar winners or nominees. From cinematographer Leo Tover (Journey to the Center of the Earth, 1959) to editor William Reynolds to art directors Addison Hehr and Lyle R. Wheeler. Wheeler also worked on The Fly (1958), The Alligator People, Return of the Fly, Journey to the Center of the Earth (all 1959) and Marooned (1969). Set decorator Thomas Little worked on Dr. Renault’s Secret (1942, review). Makeup artist Ben Nye did makeup for The Fly, The Alligator People, Journey to the Center of the Earth, The Lost World (1960), Way… Way Out, Our Man Flint, Fantastic Voyage (all 1966), In Like Flint (1967), Planet of the Apes (1967), as well as the TV series Batman and The Green Hornet in the sixties. Nye also founded a very successful makeup company catering primarily for the movie and TV business that’s still active today. Together the film team racks up over 20 Oscar wins and dozens of nominations.

One whose legacy may tower larger than the rest’s however, is composer Bernard Hermann, Oscar winner and one of the most influential film composers in history. Born Max Herman in New York, Hermann was already a force to be reckoned with in radio and as a symphony conductor, as well as modern composer. He had already been Oscar nominated for his work on Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane (1941) and been awarded an Oscar for All that Money Can Buy the same year. He was a frequent Orson Welles collaborator in radio and after The Day the Earth Stood Still he composed seven films for Alfred Hitchcock, including Vertigo (1958), Psycho (1959) and Marnie (1963). He also made the electronic bird sounds for the music-less The Birds (1964). He composed for Journey to the Center of the Earth and the Ray Harryhausen films The 7th Voyage of Sinbad (1958), The 3 Worlds of Gulliver (1960), Mysterious Island (1961) and Jason and the Argonauts (1963). Other credits include Cape Fear (1962), Fahrenheit 451 (1966), and his last film Taxi Driver (1976). His aggressive, fear-inducing, minimalist score for Psycho, made with strings only, changed not only the history of film score, but classical music as a whole, ushering in minimalists like Philip Glass and the serialist composers. The high-strung, screeching strings of the shower scene is still one of the most recognisable musical moments in cinema history.

Hermann’s score for The Day the Earth Stood Still is best remembered for its frequent use of the theremin – actually two theremins – to give the movie an unearthly soundscape and a feeling of tension and fear. This was the film that thrust the theremin onto the sci-fi and horror genre, to the extent that it quickly became a cliché and soon could only be used for comical effect. But back then, before the age of electronic music, it was truly novel and stirring, unlike any instrument the movie-goers had heard before. Or – some of them might actually have heard it, that is if they went to see Rocketship X-M (review) in 1950, where Ferde Grofé Sr. was the first composer to use it in a movie score. Below you can watch the Russian inventor Lev Termen (or Leon Theremin, as his name was westernised) play his instrument. The theremin artist on the film was Samuel Hoffman, who became synonymous with the theremin sound of fifties sci-fi movies.

But even without the theremin, Hermann’s score is memorable. Hermann refused to be cramped by the traditional symphony orchestra, and instead always put together a special setup for all his film scores. In Psycho he threw out all instruments but the strings. In The Day the Earth Stood Still he switched the analogue strings for electric ones, added four harps, an electric organ, two Hammond organs, three vibraphones, glockenspiel, marimba, electric piano, trombones, trumpets, electric guitar, among others. The music follows the story seamlessly, leaving large portions silent, only to build up suspense with repeated minimalist ostinati and punctuating dramatic moments with huge polyphone sound masses, or displays uncertainty and fear with atonal, quivering sound carpets. The score was nominated for a Golden Globe, but snubbed by the Oscars, perhaps because of the film’s genre, perhaps because of its politics. The film was, however awarded a special Golden Globe for its promotion of international understanding.

The visual effects of the film, as mentioned earlier, were the best that money could buy at the time – from the clever mix of stand-ins, inserts and rear screen projection of Klaatu and Bobby in Washington, to the glowing saucer landing on the baseball field, to Gort’s disintegration ray, disappearing soldiers and melting tanks. Much of this is thanks to special effects man Fred Sersen and his team, including L.B. Abbott. Sersen won two Oscars, as did Abbott. Abbott later led his own team on films like The Fly, Journey to the Center of the Earth, The Lost World, Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea, Way… Way Out, Our Man Flint, Fantastic Voyage, In Like Flint, Planet of the Apes, Beneath the Planet of the Apes (1970), Escape from the Planet of the Apes (1971), Battle for the Planet of the Apes (1973) and Logan’s Run (1976). He also worked on a number of TV series, including the sixties version of The Green Hornet, Batman, The Land of the Giants and The Planet of the Apes.

The Day the Earth Stood Still might have a slightly garbled moral and some rather obvious Jesus parallels, which is simply so clichéd that it always gets a slight minus in my books. The problems with Gort takes some toll on the otherwise superbly constructed feeling of authenticity and realism. These, among with other minor problems, prevent the movie from getting full ten stars from me. But nevertheless, the movie is one of the best, if not the best, science fiction film of the fifties – an intelligent, politically risky, well written, well acted, well scored, extremely well directed and designed film that along with The Thing from Another World raised the bar for science fiction films to come. Few fifties sci-fis came even close to the quality of this film.

Janne Wass

EDIT: October 5, 3016: Commentator Dan Hood rightly points out that Patricia Neal more or less reprised her role in a British low-budget ripoff of The Day the Earth Stood Still in 1954, called Stranger from Venus. The information has been added to the article. Thanks Dan!

The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951). Directed by Robert Wise. Written by Edmund H. North. Based on novella Farewell to the Master by Harry Bates. Starring: Michael Rennie, Patricia Neal, Hugh Marlowe, Sam Jaffe, Billy Gray, Frances Bavier, Lock Martin, Richard Carlson, David McMahon, Snub Pollard, Stuart Whitman. Music: Bernard Hermann. Cinematography: Leo Tover. Editing: William Reynolds. Art direction: Addison Hehr, Lyle R. Wheeler. Set decoration: Claude E. Carpenter, Thomas Little. Costume design: Travilla, Perkins Bailey. Makeup: Ben Nye. Production manager: Darryll F. Zanuck. Second unit director: Bert Leeds. Visual effects: Fred Sersen, L.B. Abbott. Robot builder: Malbourne A. Arnold. Produced by Julian Blaustein for Thwentieth Century-Fox.

Article is missing information on the 1940’s British version of Day the Earth Stood Still, possibly under another title but also starring a very young Patricia Neal who is revived by the spaceman after an auto accident.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for your comment! I think you’re getting your decades mixed up, though. Patricia Neal started her film career in 1949, and neither of the four films she made that year were sci-fis. She did, however, star in a British film called Stranger from Venus in 1954 (http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0047529), which is a low-budget ripoff of The Day the Earth Stood Still. It’s fairly well made despite its minuscule budget, and a rather charming little movie. The filmmakers have changed the plot just enough so that they don’t have to give any credit either to Harry Bates or the original screenwriters, and thus can’t really be called a “British version of The Day the Earth Stood Still”, but rather a blatant ripoff of the movie. But you are right that it probably warrants a comment. I’ll get to it. Thanks!

LikeLiked by 1 person