∗∗∗∗∗∗∗∗∗∗

(6/10) In a nutshell: Screenwriter H.G. Wells, producer Alexander Korda and director William Cameron Menzies take us on an epic journey through the future in this pompous 1936 social prophesy. The most expensive film ever made in Britain in 1936, Things to Come boasts incredible sets and miniatures, great effects, high quality filming and a team of great actors. But ultimately the movie trips on its clay feet, which is the impossibly stiff script, lacking in emotion and real dialogue. Wells is using his biggest sledgehammer to pound in his message, and prevents the audience from doing any thinking for themselves.

Things to Come. 1936, UK. Directed by William Cameron Menzies. Written H.G. Wells, based on his own novel The Shape of Things to Come. Starring: Raymond Massey, Edward Chapman, Ralph Richardson, Margaretta Scott, Cedric Hardwicke. Music: Arthur Bliss. Produced by Alexander Korda for London Film Productions. Tomatometer: 92 %. IMDb score: 6.8

In the future the world will be ruled by stiff philosophers decked out in gowns and big shoulder pads.

Things to Come was Great Britain’s most impressively epic science fiction film to date – without even a close rival – when it came out in 1936. It had a budget of about 350 000 pounds, equal to about 21 millions today; an absolutely astounding amount of money to put on a film back in that day. And thus it would remain all the way to 1968 when Stanley Kubrick made 2001: A Space Odyssey in London. Penned by the 70-year old sci-fi master H.G. Wells from his own 1933 novel The Shape of Things to Come, it was however more an ideological treatise and a futuristic prophesy than a dramatic film. Although time has conjured up a good deal of latter-day apologetics who hail Wells’ vision and – rightly so – praise the production design, the simple truth of the matter stands: Wells was an awful screenwriter.

I have written a smaller essay on the socialist pacifist thinker H.G. Wells in my chapter on the literary origins of science fiction, please read it for more information on this remarkable man, who – don’t get me wrong – also happens to be one of my very favourite authors. Therefore, to make things simple for me this time, I shall quite ruthlessly borrow a brilliant condensation of the man and his career from Richard Scheib, the author of the website Moria – Science Fiction, Horror and Fantasy Film Reviews:

H.G. Wells (1866-1946) is one of the founding fathers of modern science fiction. The peak of H.G. Wells’s success, at least as a science-fiction author, was during the first decade of his publishing career, 1895 to the early 1900s. During this time, Wells published major works and laid down what are today still some of science-fiction’s major thematic preoccupations – The Time Machine (1895), which created the idea of the time machine and set in place much of the time travel story; The Island of Dr Moreau (1896), which, even though it did not name such, laid down many of the themes of the modern genetic engineering story; The Invisible Man (1897), the first invisible man story; The War of the Worlds (1898), the first alien invasion story; and When the Sleeper Awakes (1899), the first story in which a cryogenic sleeper awakes to encounter a future society.

What many readers who come to H.G. Wells through his science-fiction do not realise is that after around 1905, H.G. Wells fairly much abandoned the scientific romances that made his name and are his most popular works. H.G. Wells’s output of the decade ahead began to move towards serious fiction /…/ as Wells attempted to establish himself as a serious novelist. For the bulk of the rest of his career up until his death in 1946, Wells became an ideologue. During this time, Wells began to write essays on futurology and dedicated himself to finding a means of improving the world through scientific progress.

By 1933 H.G. Wells was something of a optimistic pessimist, if that makes any sense, and was writing daunting ideological-philosophical treatises on history, economics, and the future. WWI cemented his views of pacifism and he was terrified as he saw fascism on the rise in Europe, and the Great Depression of 1930 probably didn’t make the world look any more cheerful. In his 1933 novel The Shape of Things to Come he outlined a hundred years of future, starting with a second world war in 1940 and ending with the first trip around the moon in 2036.

It was this story that Hungarian-born British master director and producer Alexander Korda wanted to put on the screen almost as soon as the book was published. And in a brilliant coup (or so he thought) he got Wells to write the screenplay. But there were a few problems. First of all Wells had never written a screenplay for a feature film. Second, Wells hated science fiction movies. Third, the 70-year old author was by now much more interested in lecturing than entertaining. For a bit of a dramatic touch, the two also drew from Wells’ 1897 story A Story of Days to Come. As not to make it too enjoyable, they also added bits from Wells’ economic and social treatise, The Work, Wealth and Happiness of Mankind (1931). It took two and a half years and four different drafts, with significant help from Korda to get something that resembled anything that could be put on screen. And this was when production begun, in 1935.

Korda himself was having trouble enough producing, and wanted to hire another director. Since the script called for an until then unprecedented (in Britain) vision of a futuristic world and a number of giant sets, miniatures, mass scenes and elaborate models, Korda went for a man whose background wasn’t mainly in direction, but in production design. In fact, American William Cameron Menzies was the man they invented the title ”production designer” for – as opposed to merely calling him ”art director”. Menzies had impressed Korda hugely with his design visions in films like The Thief of Bagdad (1924), The Dove (1927) and The Tempest (1928) – the two latter earned him a combined Oscar in the first ever Oscar ceremony in 1928. By 1934 he had also directed six movies, perhaps most famously the 1934 Bela Lugosi vehicle Chandu the Magician.

To design the lavish sets and models, Korda hired his own brother Vincent, who had already cut his teeth on elaborate period dramas like the Oscar-winning The Private Life of Henry VIII (1933) and The Rise of Catherine the Great (1934). It is unlikely, however, that Menzies didn’t design much of the film himself. Much has been made of the fact that Korda also hired the modernist artist and Bauhaus engineer László Moholy-Nagy to design some of the future city of Everytown, but his involvement was ultimately cut down to a 90 second scene of a man behind a sheet of corrugated plastic. Another common misconception is that H.G. Wells had more or less the final say in all decisions regarding the film – the fact is that he was made to believe he had, but ultimately he didn’t have much say in matters at all, the script excluded. He is said to have been on set constantly, exacting on many small details, but when the film was finally released, it had been cut down from 130 to 108 minutes, without consulting Wells, and was further cut down to 94 minuted in the US.

The plot, such as it stands, is cut up in three chapters. First we visit the near future Christmas of 1940 in the city of Everytown – a not very subtle metaphor for London, where John Cabal (Raymond Massey) and his friend Harding (Maurice Braddell) find it hard to get into the holiday spirit with the threat of war looming. The philosphical pacifist Cabal worries that war in Europe will spred to Everytown, but the jolly Pippa Passworthy (Edward Chapman) doesn’t let little things like wars dampen his spirits. And indeed WWII comes with an air raid, and impressive, crowded scenes of war and panic in the expressionistic, dark Everytown.

We next see Cabal as a fighter pilot having just crashed along with an enemy, and together they save a girl and lament the futility of war.

Move on to 1970, when WWII is still sputtering on, but now as a low-intensity local tribal war in a post-apocalyptic future, bombed back to – if not the Stone Age, then at least the Dark Ages. Everytown in now ruled by a despotic bully who calls himself The Boss (Ralph Richardson), and bears a striking resemblance to Benito Mussolini – or as New York Times critic Frank S. Nugent put it in 1936: ”who might be mistaken for a comic opera despot, except for his impious resemblance to certain internationally prominent figures of today”. In addition to this, the war-weary population is haunted by a plague caused by a chemical weapon called the wandering sickness, which basically turns them into zombies, and they are therefore shot on sight. Dr. Harding is now desperately working on a cure with his daughter Mary (Ann Todd). The Boss is driven around in a horse-pulled old car and desperately searches for gasoline and engineers who can repair his old planes, so he can take up the fight with the mountain guerillas that are hounding his rule.

Enter the aged Cabal in a futuristic Flash Gordon-esque airplane and a strange black uniform reminiscent of Mars Attacks (1996). Cabal is now a captain of the world government called The Wings over the World: ”the Freemasonry of Efficiency, the Brotherhood of Science”, and he calls for an end of all hostilities and the capitulation to the new world order, based on philosophy, scientific progress and pacifism. The Boss and his queen Roxana (Margaretta Scott) will of course hear nothing of it, and instead make Cabal their prisoner, and demand he start repairing their old biplanes, which he obediently does, but just until The Wings over the World arrive in their gigantic futuristic airplanes, and start dumping ”peace gas”.

Then we get to the film’s best part: a long montage showing the rebuilding of Everytown as a futuristic, white, clean, functionalism-inspired underground city with large Soviet-like statues depicting the man of the future. The montage is jam-packed with impressive miniatures and sets, mechanical models, and people in futuristic suits going about in futuristic labour-machines. Matte paintings, double exposures, back projection and montage techniques are used heavily – and the scale of it all nearly eclipses Metropolis (1927, review).

In 2036 the new world government has eradicated not only poverty and illness, but also religion and inequality, it would seem, as well as democracy. People now live exclusively in underground cities and spend their time watching television and strolling in air-conditioned shopping malls. The ruler of Everytown in now Cabal’s grandson Oswald Cabal (Massey) – a benevolent dictator basing his rule on science and equality. This was Wells’ vision of a perfect world: a world ruled not by the majority of the people, but by an elite of philosophers, very much in the vein of Plato’s thinking. A plutocracy of the wise and good, if you will. The talk of the hour in Everytown is the coming trip around the moon – by means of a ”space gun” (basically the old Jules Verne idea of shooting a spacecraft out of a cannon).

But dissatisfaction brews within the ranks of the luddites led by the scupltor Theotocopulos (Cedric Hardwicke), who feel that the new world is too ”white, too clean”, and that ”there must be and end to this progress” so that one might go back to living instead of preparing for living. Here Wells engages in the faux argument between science and art; the artists for some reason rise up to protest against Wells’ planned society. The film ends with a debate of monologues between Theotocopulos and Cabal at the hour of the moon flight, which naturally Cabal wins by claiming that progress, as well as the debate about it, must go on for eternity so that man can keep on perfecting himself. Off go the astronauts. Applause all around.

There are some different ways to tackle Things to Come. One may first and foremost see it as Wells’ prophesy of the future. This interpretation has been given credit mainly because of the fact that he was able to predict World War II and its aftermath with such precision – especially the hardships the war would bring for the civilian population. Wells also foresaw the television and the shopping mall.

But in truth, Wells was always more of an ideological speculator than a scientific predictor. And when one starts to look closer at the film, he actually scored more misses than hits with the film. That a war was coming was not difficult to predict in 1933, nor were TV and shopping malls. Malls were already going up across the world and the technology for television had been around for quite some years, even if there still wasn’t a practical application for the public. There are also a whole bunch of stuff he got wrong, like the first trip around the moon – off by 70 years, and in reality we actually landed. And why on Earth did he use the idea of a ”space gun” when scientific community was at this time pretty clear on the fact that any outer space trip would have to rely in liquid-fuelled rockets? Or the idea that nobody wants to go outside in 2036, because it is just silly to need fresh air and sunshine when you can live in a white plastic city underground. I mean, imagine the cost and resources for sustaining a whole population in caves, when we hardly even fit on the surface – overpopulation was clearly not a problem that concerned Wells.

The idea that scientists and philosophers would form a new world order was something that probably even Wells didn’t believe, but rather wishful thinking on his part – in this sense he shows us what he hoped the world could become, would we play our cards right. Ideologically there is much in Wells’ vision one happily subscribes to – that the basis of a new world order would have to be science, equality and and cooperation. Note that he omits the word freedom, which any American would probably not have done, as well as democracy. Also note that The Wings over the World in their black uniforms, ordering people around, telling them what and how to think have an eerie resemblance to a certain national-socialist party that would set the world on fire just a couple of years later. It also seems that a new world order would have to rely on a strong ruler – a benevolent dictator chosen from a small group of philosophers, rather than from a democratic society.

In this way Wells was closer to the idea of Stalinism than he maybe was prepared to admit to himself (he famously lectured Stalin on how communism was supposed to be done). So even if Wells is delivering his ideology with a hammer (perhaps wisely passing on the idea of combining it with a sickle), and the film is basically a long monologue on the virtue of a scientifically based pacifism with socialist undertones – the ideology he presents is quite naive and a bit disturbing, at least watched in retrospect. The clinically clean and healthy world he presents as the intended future of the human race does eerily resemble not so pleasant outlooks, like those presented in films like Logan’s Run (1976) or The Island (2005). There also seems to be an omission of anything resembling a class struggle, a problem that seems to be getting worse by every year these days – in this sense his vision outlined in The Time Machine was more spot on. But again – this was his utopia, not necessarily his prediction.

As stated, the film is visually stunning, and Korda/Menzies have clearly studied both the biblical epics of Cecil B. DeMille, German expressionists like Fritz Lang (Metropolis) and F.W. Murnau (Sunrise, 1927), as well as Russian montage theorists like Lev Kuleshov (The Death Ray, 1925, review) and Sergei Eisenstein (Battleship Potemkin, 1929). The editing of the film is really the only thing that is dynamic and really exciting in this movie – not too surprising since Korda makes use of two future Oscar winners (William Hornbeck and Francis D. Lyon) and one Oscar nominee (Charles Crichton). Especially the shots of war in 1940 and the future montage still holds up today as some of the best of the era.

The dark proto-noir look of Everytown in 1940 is stunningly beautiful, and it is impossible not to draw a straight line from these scenes to Ridley Scott’s vision of Los Angeles in Blade Runner (1982). But then as we move towards 1970 things start getting a bit silly. The costumes of the future city rulers look like ripped from Mad Max II: The Road Warrior (1982), and what on Earth was costume designers René Hubert and John Armstrong thinking when they designed that collar on Cabal’s uniform? Things get even sillier in 2036, when we have now regressed to some sort of Neo-Grecan style, no doubt inspired by the many costume dramas of the era (as well as Wells’ obsession with Plato), with urbanites wearing Greco-Roman-inspired shorts, capes and gowns, along with the standard sci-fi look of impossibly broad and impractical shoulder puffs. If anything, the costumes of future Everytown resembles Flash Gordon (1936, review). Why do people always think we’ll dress like idiots in the future?

The filming is good, although Menzies is more interested in showing off the sets and models than doing anything with the actors. This gives the film a static feel, and swinging the camera around a bit more would have created a greater dynamism in the movie. But future Oscar-winning French cinematographer Georges Périnal does a great job with what he’s got, and what he’s got are some impressive sets and miniatures, and those he certainly knows how to light and shoot. The shots of moving models are sometimes a bit shaky and clumsy, but that may be forgiven.

The big problem with Things to Come are not on the technical or artistic side, though. It is the script. Wells sets out to give an epic vision of the future, an ideological firebrand for peace, scientific planning and harmony in a seriously fucked-up world. And so he does, but the problem with his futuristic vision is that people don’t have much room in it. This dialectic epic doesn’t give the actors any chance to actually interact with each other, and the dialogue consists mainly of haughty monologues representing different sides of an argument. And even the argument is faux, as Wells doesn’t bother to try and understand the opposition at all. His righteous lead Cabal is domineering, self-righteous and pompous, and all who oppose his ideas are basically dim-wits. It’s not hard to take the side of scientific and equal brotherhood when your main antagonist (The Boss) spouts rants like a dime-store copy of Il Duce. Theotocopulos’ arguments are hollow and dumb. No luddite has ever opposed progress for the sake of opposing progress. Luddites (or neo-luddites) oppose certain progress on the basis of the perceived outcomes of this progress – such as in the case of the original luddites, that technology would make textile workers unemployed. There are certainly cases to be made for technological scepticism, degrowth and postdevelopment theory, but Wells feels no need to try and understand these notions. For him it’s a case of everything or nothing, in the closing words of Cabal: ”If we’re no more than animals, we must snatch each little scrap of happiness and live and suffer and pass, mattering no more than all the other animals do or have done. Is it this? Or that? All the universe? Or nothingness? Which shall it be, Passworthy? Which shall it be?” It is, plain and simple, a propaganda film.

The argument for a peaceful society based of science and equality is still compelling today – although we might envision it slightly different than the stuffy elitist British upper-class slant that Wells and Korda put on it. Korda was a passionate defender of the old British royalist society, which clashed with his director brother Zoltan, who was more of a liberal socialist, like indeed Mr. Wells. Thus, all the blame for the very top-down ruled society of the future depicted in the film shouldn’t perhaps be directed at Wells, but also at Alexander Korda (though Wells was always more interested in the intellectual middle-class side of socialism, rather than with the working masses).

There is also something to be said about the futuristic vision of a strictly Caucasian society – and some casual sexism in the film with seems a bit jarring by today’s standards. But we can perhaps put this down to the standards of 1935.

H.G. Wells didn’t like science fiction films – and indeed there were not very many of them worthy of liking of you wanted some sort of intellectual stimulation in 1936. One that might have been to his liking – a socialistically tinted epic future vision of the class struggle – Metropolis – he called ”the silliest of films”. But what Fritz Lang’s epic has going for it, that Things to Come doesn’t, is interesting characters, human interaction. Simply: a heart to go with the head. (Another reason that Wells hated the film was that screenwriter Thea von Harbou was a techno-sceptic.)

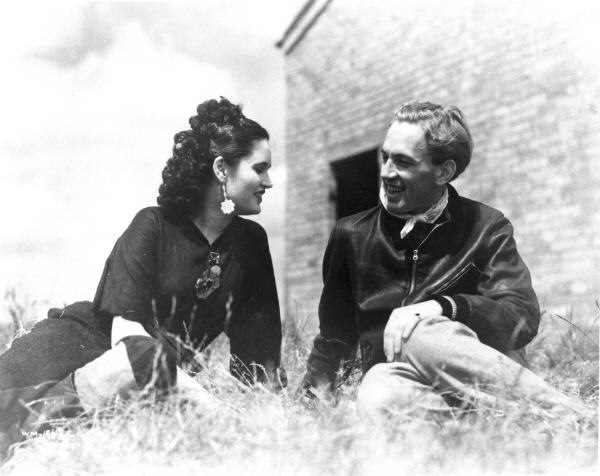

Margaretta Scott as Roxana and possibly John Clements or Maurice Braddell in conversation – between shooting – conversations in the film were never this relaxed.

There is a line to be drawn between Metropolis, Things to Come and 2001: A Space Odyssey. All three deal with the human condition and the future of man through the lens of epic, bombastic science fiction. But of these three, Things to Come is the one film that doesn’t require any independent thought from the viewer. There is not a single character in the film that we actually care about, which makes this an intellectual exercise, but an exercise where Wells does all the thinking for us. That we can pick his vision apart today in hindsight is no excuse for making an intellectually flat movie. And indeed, this is once again in line with Wells’ social vision. In his mind, democracy was a flawed system. According to Wells the people cannot make choices for themselves, but the choices must be made by an enlightened elite. Thus he is telling us what to think even in his film.

One might think that a cast including Raymond Massey, Cedric Hardwicke and Ralph Richardson would be something of a wonderful clash of acting royalty – all three being renowned theatrical actors. But instead we get stiff, pompous speeches and a lot of dictating to the heavens. Massey once complained about the lack of humanity and emotion in the script by saying ”For heart interest Mr. Wells hands you an electric switch”. That Wells’ vision was in many ways extraordinary, and that the filmmakers were able to visually formulate it with such grandeur is the film’s saving grace.

There have been almost 100 straight film or TV adaptations of Wells‘ books, and his influence of the genre is naturally immense. From Georges Méliès’ groundbreaking sci-fi film A Trip to the Moon (1902, review) to the 2005 Steven Spielberg blockbuster War of the Worlds, starring Tom Cruise, Wells’ vision has continued to inspire filmmakers. Unfortunately the author’s social commentary has often been not only omitted, but sometimes even reversed in the filmmaking process. One can only be grateful that the pacifist atheist Wells was no longer around to see the tacked-on military and religious pathos in the 1953 film The War of the Worlds (review). Thus it is a shame that this one film where his ideas are given full attention is such a preachy bore – and I am sure the young Wells would have agreed with me. The beauty of his early novels and short stories is that these ideas are brought forth as metaphors, almost hidden in the exciting tales he is telling – and this is ultimately why Wells is the legend he is today. We need both heart and head, both juvenile distraction and adult intellectualism. Remove one side, and any film becomes lopsided. And quite naturally, the audience also shunned Things to Come when it was released, and it received mixed reviews from the press.

William Cameron Menzies was famously the first person to be called ”production designer” rather than ”art director”, to emphasise that he was often responsible for the whole look of the film, rather than just a set designer. With his great vision and his experience not only as a designer, but also in direction, he was held in great esteem by producers and directors both in Britain and in Hollywood. In the making of the 1939 classic Gone with the Wind (9 Oscar wins), director Victor Fleming is quoted as having said to all departments that ”Menzies’ is the final word”. He also directed the famous sequence in the film of the burning of Atlanta (”Atlanta” here meaning the native’s wall from the 1933 film King Kong [review]). Menzies would return to science fiction once – as director and production designer on the hilarious 1953 classic Invaders from Mars (review).

Raymond Massey was sought-after Canadian stage actor, who is perhaps best known for his portrayal of Abraham Lincoln, whom he played in four different stage, film or TV adaptations, one of which was Abe Lincoln in Illinois (1939), for which he received an Oscar nomination. Things to Come was his only sci-fi appearance. Stocky English character actor Edward Chapman (the hedonistic Passworthy) appeared in over 100 films or series, of which one other was a sci-fi: the 1956 film X: The Unknown.

Ralph Richardson was just breaking into his stardom in 1936, as he would later dominate the British stage along with contemporary Laurence Olivier. Like Olivier, he was also a prominent film actor, and appeared in over 60 films. He was nominated for an Oscar twice, once as late as 1985 for his supporting role in Greystoke: The Legend Of Tarzan, Lord Of The Apes, acting alongside Ian Holm (Alien, 1979, Frankenstein, 1994), Andie McDowell (Muppets from Space, 1999) and Christopher Lambert as Tarzan (the Highlander series, the Fortress series, Mortal Kombat, etc). Richardson won numerous awards for his stage and film work, including BAFTA, Saturn, Cannes and New York Film Critics Circle Awards. The Saturn Award came for his role in the 1981 fantasy film Dragonslayer.

Cedric Hardwicke carved out a respectable career in Hollywood, starring in many genre films in the thirties and forties, including The Invisible Man Returns (1940, review), Invisible Agent (1942, review), The Ghost of Frankenstein (1942), The War of the Worlds (as the narrator, 1953), The Unkwown (1964), as well as the TV-series The Twilight Zone (1959) and The Outer Limits (1963). Interestingly enough, Hardwicke was brought on at the last moment. The role of Theotocopulos had been slated for British veteran actor Ernest Thesiger, famous for his role Pretorius as in Bride of Frankenstein (1935, review). Thesiger had already filmed all scenes save one, when Menzies thought he wasn’t right for the role.

Charles Carson (in a small supporting role as great-grandfather in the beginning of the film) later appeared in the TV-series Avengers (1961) and The Curse of the Fly (1965). Derrick De Marney (as Richard Gordon) again touched upon sci-fi in his last film, The Projected Man (1966). Sophie Stewart (as Mrs. Cabal in the beginning) appeared in the aptly named Devil Girl from Mars in 1954 (review).

In a small bit-part as a pilot we see the beloved film and TV actor George Sanders, who would later appear in the sci-fi films From the Earth to the Moon (1958), Village of the Damned (1960), The Body Stealers (in the lead, 1969), Doomwatch (1972), and in the TV-series Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea (1965) and as Mr. Freeze in the legendary Adam West-fronted Batman series in 1966.

Another bit-part player, the later beloved comedian Terry-Thomas incidentally played in another adaptation of Jules Verne’s moon adventure: Jules Verne’s Rocket to the Moon (1967), as well as in 2000 Years Later (1969) and The Mouse on the Moon (1963). Adam Sofaer as The Jew was a noted stage actor who appeared in many period dramas, and who after appearing in The Twilight Zone became something of a staple in sci-fi series, including The Outer Limits, The Time Tunnel (1966-67), Lost in Space (1968) and Star Trek (1966, 1968). He also appeared in the movie Journey to the Center of Time (1967).

Interestingly enough, very few of the technical or artistic staff worked on other sci-fi films. An exception is special effects photographer George J. Teague, who was a ”technical effects creator” on the hilarious giant turkey film The Giant Claw, which basically means he co-created the worst movie monster ever put on screen. Notable, though, is one young cameraman called Jack Cardiff, who would later become known as one of the great British cinematographers, and won an Oscar for his work on Black Narcissus (1947), and another honorary Oscar in 2001. He is renowned for his work on films like War and Peace (1956) and Sons and Lovers (1960), but for us lovers of genre film he is probably most important as the photographer of Conan the Destroyer (1984). Of course the other cameraman on Things to Come, Australian-born Robert Krasker thought he wasn’t going to be out-oscared by some limey, so he went and got his own Academy Award for The Third Man (1949).

So with all its flaws and successes, where does this film stand in the broader history of science fiction films? Well, one might say that it is an anomaly. Historically it stands alone in Britain, nothing like it was made before, or for many decades after in the country. Unlike Metropolis, that spawned German epic-ish films like Gold (1934, review) and Master of the World (1935, review), or 2001: A Space Odyssey, that set the tone for the sci-fi genre for a decade after its release, Things to Come spawned nothing. It came, it awed, and it went quietly away (partly because of the war, of course).

Some commentators have called it ”one of the most important sci-fi films in history”, which simply isn’t true on any level. It was not nearly the first social-commentary sci-fi film: many had come before, starting with the Danish The End of the World in 1916 (review). Its epic style had been used for decades, even in sci-fi, and Metropolis did it with a more pioneering visual style ten years earlier. The vison of the future architecture and design were more or less copied from comic strips and newspaper spreads on ”what will life be like in the year 2000?”. I haven’t heard or read a single director, screenwriter or producer say they were ”inspired by Things to Come” (although one can find similarities in Vincent Korda’s planes and some of the vehicles in Star Wars), neither is it a film that people draw parallels to, unless when commenting on the stiff propaganda tone of the movie. Of course, this in and of itself doesn’t take away any of its actual qualities, that are there in abundance for anyone to see.

Cabal stands over the fallen Boss, who could not stand the happy thoughts brought on by the peace gas.

The problem is perhaps that this is not a film that people are passionate about. We see its merits, but few remember it fondly from watching it on Saturday morning TV matinees or remember the sense of awe when they first saw it. People are passionate about silly things like Flash Gordon or Star Wars – they are important in the history of sci-fi films. People are equally passionate about heavy films like Metropolis or 2001. Things to Come is certainly a well-made film in many respects, and it is likewise an intelligent film, a film that there has been put a lot of thought and passion into making. Technically it is nearly flawless. But a film is not a machine – it isn’t enough that it is efficiant and well built. A film should also speak to your emotions, and for that you ultimately need a wonder that goes beyond the intellect – it needs a heart and a soul, and real people who bring these things to the screen. That is ultimately what this film lacks, and that is the reason it will always stand in the shadow of the giants.

Things to Come. 1936, UK. Directed by William Cameron Menzies. Written H.G. Wells, based on his own novel The Shape of Things to Come. Starring: Raymond Massey, Edward Chapman, Ralph Richardson, Margaretta Scott, Cedric Hardwicke, Maurice Braddell, Sophie Stewart, Derrick DeMarney, Ann Todd, Pearl Argyle, Kenneth Villiers, Ivan Brandt, Anne McLaren, Patricia Hillard, Charles Carson, George Sanders, Abraham Sofaer, Terry-Thomas. Music: Arthur Bliss. Cinematography: Georges Périnal. Camera: Jack Cardiff, Bernard Krasker. Editing: William Hornbeck, Charles Chrichton, Francis D. Lyon. Costume design: René Hubert, John Armstrong. Production management: David B. Cunynghame. Art director: Vincent Korda. Special effects: Ned Mann, George J. Teague, Edward Cohen, Ross Jacklin, Hary Zech. Visual effects: Jack Cardiff, W. Percy Day.

17 thoughts on “Things to Come”