∗∗∗∗∗∗∗∗∗∗

(0/10) In a nutshell: Exploitation director Ron Ormond built a new film on top of a completed, but shelved production by German wannabe director Herbert von Schoellenbach. Uncle Fester stars as a mad scientist creating spider women in a cave in a mesa, where a ragtag group of heroes and villains crash their plane after being kidnapped by a madman. There are giant spider props, mute and sultry spider girls, evil dwarves, a Chinese valet who speaks in proverbs, a mad one-eyed scientist, and by some miracle it all adds up to one of the most boring films in history. Worse than anything Ed Wood ever made. But still strangely compelling.

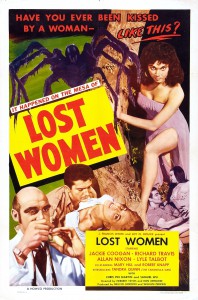

Mesa of Lost Women (1953). Directed by Herbert Tevos (Herbert von Schoellenbach) & Ron Ormond. Written by Herbert Tevos & Orville H. Hampton. Starring: Jackie Coogan, Paula Hill, Robert Knapp, Tandra Quinn, Harmon Stevens, Nico Lek, George Barrows, Allan Nixon, Richard Travis, Lyle Talbot, Chris-Pin Martin, Samuel Wu, John George, Angelo Rossitto. Produced by Melvin Gordon & William Perkins for Ron Ormond Productions. IMDb score: 2.5

The most prevalent description of this bewildering tale is ”a really bad fever dream”. Another fitting attribute is ”something approximating a full-length feature film”. Like Invasion U.S.A. (1951, review), sitting through this one is a test of endurance, but no matter how much I loathed that film, at least it had one good performance and something resembling a cohesive plot. Mesa of Lost Women has no such redeeming qualities. It’s one of those films that you love after seeing it, because it’s so ridiculously bad, but sitting through it is a nightmare. I am not above giving bad movies good reviews when they deserve it, as I should have proved with my five-star rating of Robot Monster (1953, review). Although I love Mesa of Lost Women to bits for being so horrendously bad as it is, it would be a crime against cinema as an art form to give this film any more than zero stars. That doesn’t mean that you shouldn’t watch it, because you should. Just like you should go winter bathing at least once in your life. You’ll hate every minute of it, but you’ll be so happy once it’s done.

This is not just one of the worst movies ever made – it’s actually two! In 1950 production began on a film called Tarantula, written and directed by one Herbert Tevos (we’ll get to him later). However, the finished film was deemed unreleasable, so it just sat there. A year later the rights to the film was picked up by Howco Productions, who hired Ron Ormond, by that time best known for his cheap Lash Larue westerns, to film additional scenes in order to make it ar least ”approximate a full-length feature film”.

Nothing makes any sense in this movie, but I’ll try and give some fair ”approximation” of the plot. The film opens with a ragged young couple dragging themselves through a desert. They keep walking for a good five minutes while a brilliant Lyle Talbot delivers a neverending narration that would make Vincent Price seem understated and subtle, about how puny and foolish Man is, thinking he owns the world; ”Consider, even the lowly insect that man trods underfoot outweighs humanity several times and outnumbers him by countless billions. In the continuing war for survival between man and the hexapods, only an utter fool would bet against the insect.” And this just goes on and on and on as Lyle Talbot kills time by listing all the modern conveniences that this couple has left behind the venture into the Muerto Desert … The desert of DEATH: roads, air-conditioned automobiles, electrics … statistics (?) … until finally they are picked up by an American oil prospector and his colleagues in a jeep.

There is no way I can explain the plot in any chronological way and still make it have sense, since it is told in flashbacks within flashbacks, so here it is, sort of straightened out: The film concerns a Dr. Araña (Jackie Coogan), who lives in a cave in the Zarpa Mesa in the desert of DEATH in Mexico, where he is injecting spider venom into the pituitary gland (what would horror films do without the pituitary gland?) of women – and vice versa? Thus he creates a race of superwomen, who are also mute and constantly sultry and obey his wishes. The men turn into dwarves and the spiders get big as dogs. One day he sends for a Dr. Masterson (Harmon Stevens) to help him with his work, but Masterson freaks out, gets injected with something, escapes, goes crazy, gets locked up in an insane asylum and escapes to a honky-tonk on the border of Mexico.

Here he meets rich old Jan van Croft (Nico Lek) and his gold-digger wife Doreen (Paula Hill), whose plane has broken down, and who are accompanied by manservant Wu (Samuel Wu) and pilot Grant Phillips (Robert Knapp). There’s also one of the spider women doing a very long and ”erotic” (?) dance. She is Tarantella (Tandra Quinn). Joining the party is Masterson’s male nurse George, or ”George the Male Nurse” as he is billed (George Barrows without his gorilla suit). Masterson shoots Tarantella and kidnaps the rest of the posse at gunpoint, and force them to take off in the half-functioning plane (because he is crazy, that’s why). Tarantella is seen coming back to life, because, as is explained earlier in the film, she is “indestructible” But it turns out Wu is secretly in cahoots with Dr. Araña, and has tampered with the plane and the gyrometer, so that they crash land exactly on Zarpa Mesa.

Most of the action takes place in the dark mesa by the hull of the airplane, where the posse begin to bicker and line up from left to right, struggling to all fit in the shot. There’s some romance between the pilot and the chick, romance as written by a 10-year old (which basically goes for the rest of the script as well). Sometimes one of the troupe goes wandering in the dark woods for no apparent reason and gets killed by some unseen menace, one of the spider girl, or in one instance a giant jumping spider. And while this goes on, we have some arbitrary cuts to laughing dwarves (John George and Angelo Rossitto). Eventually the survivors – Phillips, Doreen and Masterson – are taken down to the cave of Dr. Araña and his lab, where Masterson is cured and we have a little wrestling and the pilot and the chick escape while Masterson blows up the lab.

And now I will take you back again to the beginning of the film, the prologue, so to speak, which actually pics up after the adventure at the mesa. We meet Grant and Doreen wandering in the desert, as described earlier – they have now escaped the horrors of Araña. The whole movie is thus told in flashbacks. The couple is picked up by the oil prospectors (Allan Nixon and Dan Mulcahey) and their Mexican guide Pepe (Chris-Pin Martin), actually billed ”Pepe the Jeep Driver”. The only time we see him near the vicinity of a jeep he is in the passenger’s seat. Now remember – this all happens in the beginning of the movie. They are taken to the prospectors’ office, where all the actors basically stand on top of each other to fit into frame, and Phillips raves on about the superwomen and Dr. Araña’s strange experiments. And to get the movie going, he starts to tell his story: ”Well it all started at the border…” But then the narrator kicks in again, because the screenwriters have just realised that it didn’t start with Phillips, but with Masterson. But Masterson is not around for the flashback, neither is anyone else, and Phillips doesn’t know Masterson’s story. This is a conundrum. How to solve a flashback scene when all those who were involved are dead? The screenwriters solve it by giving the flashback to Pepe, who is so much a stereotype that he actually does the roly-poly with his eyes and says ”Dr. Araña, ay caramba!”. And for some reason Pepe now knows the story of Masterson, or at least that’s what is implied. We never now for sure, because all he says is ”Dr. Araña, ay caramba”. Instead Lyle Talbot implies that he does know what’s going on at the mesa. That’s when we cut to Masterson and the spider women in the desert and the movie gets going.

So there you have it. It might sound like fun and camp, with giant spiders and mad scientists and evil little people and plane crashes and spider women. But really, the overall sensation of this film is one of utter boredom. The spider women don’t really do anything spidery. The just stand around and look sultry and stiff and sometimes hold out their hands like claws. The only time you get a good look at one of the spiders, it looks like a stuffed toy you win at an amusement park, and sort of stands ashamed in a corner, where Araña hides it behind one of those screens that women change clothes behind in old movies. Another time we see the belly of a spider as it jumps van Croft. And that looks just like what it is. A big prop that some stage hand throws at the camera. Or perhaps it hung on wires. Same result. Most of the movie is just people standing in a line talking about things that we don’t really care about. Jackie Coogan, who one might think would be great, is the biggest bore of all. Coogan, who was the child protégé of Charlie Chaplin (The Kid, 1921), and later became famous for his over-the-top antics as Uncle Fester in The Addams Family (1964-1966), decided to underplay his character as much as he overplayed Fester.

As with a lot of child stars, Coogan’s career dwindled when he hit maturity, and he had a rough spot for some years, especially since his mother and step-father denied him the approximately 4 million dollars he made as a child actor. He didn’t even legally have any right to them according to California law. Because of a public uproar, California passed the so-called Coogan Act to make sure child actors’ rights were protected in the future. Coogan left Hollywood for the war in the early forties, and when he returned in 1945, his career was pretty much washed up, and he was broke, so he did a handful of B movies, and even Z movies, like Mesa of Lost Women. He transitioned into TV, but it wasn’t until the late fifties that he started getting recognised again, and it took until the early sixties before he got his second breakthrough with important roles in both McKeever & the Colonel (1962-1964), and of course The Addams Family.

As stated, one of the reasons the film has such a psychedelic structure is that it was literally one film made on top of the other. Some have speculated that Herbert Tevos had left Tarantula half-finished, but according to B movie guru Tom Weaver, who actually found and read the original script, Tarantula is essentially in Mesa of Lost Women in its entirety. According to his post at Monster Kid Classic Horror Forum – which is THE authority on forgotten horror and sci-fi films, the film basically follows ”the homicidal maniac” Masterson as he kidnaps the posse, as they crash on the mesa, start bickering, fight off some unseen menace, bicker some more, get killed by a hairy claw, get chased by some giant spiders and escape in a helicopter. The only scene that Ormond omitted was basically the final scene. The dance scene was in the original film, but in that movie Tandra Quinn was just a dancing girl, there were no spider women, no dwarves, no mad scientist, no narration. Just a bunch of people getting kidnapped by a maniac, crash on a mesa, bicker, have a lame love story and escape.

Which brings us to the writer-director of Tarantula. And please, do not confuse this with Jack Arnold’s great spider movie Tarantula from 1955 (review). That’s a whole different story. Herbert Tevos has long been something of a mystery. He was known to have written a number of unusable scripts in Hollywood, and is said to have taken a pride in omitting any kind of unnecessary sub-plots or deviations from the central idea, which explains the bare-bones proceedings of Tarantula. According to people who worked on the script, interviewed by said Tom Weaver, Tevos claimed to have been a big star director in Germany, and to have directed Marlene Dietrich in The Blue Angel (1930). According to Tandra Quinn, he had tried to make the unknown Quinn his protégé, telling her he was going to make her a star, even coming up with part of her stage name (she added the last name). How much of his bolstering the other people in the crew actually bought is unclear, but 18-year old Quinn at least bought it to some extent. In the book I Talked with a Zombie Quinn recalls: ”He tried to be my Svengali, and kinda dominate my every move. He wanted to make this exotic character out of me, and came up with the screen name ‘Tandra Nova’ for me”. Quinn changed the last name, since ”Nova” reminded her of boxer Lou Nova. Herbert Tevos never made another film in Hollywood, nor is there any record of a Herbert Tevos working on anything in Germany.

However, the great minds at Monster Kid Classic Horror Forum dug up an old comment from 2001, by Tevos’ son, who revealed that Tevos’ real name was Herbert von Schoellenbach, and that he had worked for the film manufacturer Agfa in Germany, and it was Agfa that brought him to the States. Someone even dug up some records at Agfa that mentioned Schoellenbach. Turns out Schoellenbach shared Tevos’ love for talking about himself and all the adventures he had been on (apparently as a documentary filmmaker in the Amazon jungle, among other things).

According to the files of Rochester Institute of Technology Schoellenbach was head of the paper testing department at Agfa Ansco in Binghampton, New York. Professor emeritus Ira Current recalls: ”At our gatherings Schoellenbach regaled us with his biography; his experiences as a motion picture cameraman, his expeditions to the Amazon, and his association with Richofen, the World War I German aviation ace. He had been the cameraman on an expedition up the Amazon River when everyone became ill with fever. He was able to escape, alone, back to civilization but had buried several thousand meters of exposed motion film in the jungle.” Bill Warren and Bill Thomas in their book Keep Watching the Skies claim that Schoellenbach had a ”long connection with filmmaking”, but don’t elaborate further, stating that Taratula/Mesa is his only known movie credit.

The German National archives DO actually list him as one of people having had correspondence with Karl Vollmöller, who wrote the screenplay for Blue Angel, so there might be some grain of truth to Schoellenbach’s involvement, however minuscule, in that movie. Under the Freedom of Information Act, there was released a notification of a report made by the FBI Alien Enemy Control in 1942, of the detention of a Herbert von Schoellenbach for interrogation in Los Angeles, which means he was apparently living there by that time. The documents give no further information. As a pointer of what he might have been doing after Tarantula tanked, there’s an archive of the ”Annual Reports of Yellowstone National Park Superintendents”, that lists ”Herbert von Schoellenbach, cameraman of the General Photo Sales corporation” as one of the ”distinguished guests” at the park in 1957. A family ancentry site gives Schoellenbach’s year of birth as 1896 in Germany, and places his death at 1988 in Los Angeles. The records further state that he served in WWI. There’s also a record of him registring for the draft in 1942 in Los Angeles, which may be when he was interviewed by the FBI. But that’s really all I can dig up on the elusive Herbert von Schoellenbach – although I recommend reading Tom Weaver’s interview with Tandra Quinn, who has a lot of funny anecdotes both regarding him and the making of the film.

We know a lot a more about the director of the second film, built on top of Tarantula, Ron Ormond. Born Vittorio Di Naro, Ormond started his career under the moniker Rahn Ormond as a vaudeville artist and stage magician, until he almost accidentally fell into filmmaking in the late thirties, first as a writer and producer of cheap western films, and in 1950 as a director, thanks to his friendship with western mini-star Lash La Rue. He shifted gear in 1953, when he was asked to do new footage for Tarantula, a film he claimed to have hated, and after this became known as one of he most infamous exploitation directors in the States, covering both horror and sci-fi and sexploitation and gore.

After a short break following Mesa of Lost Women, Ormond and his wife, vaudeville performer and dancer June Carr, who co-produced many of his films, made one of his most notorious films, Untamed Mistress (1956), about a woman being brought up by gorillas. It was their first roadshow film, and had a lewd marketing strategy, insinuating heavily inter-species sex, which was never carried out in the movie. Nevertheless, it was a hit, and was followed by a string of other pics, best known probably the ”frigid wife” sexploitation drama Please Don’t Touch Me (1963). After relocating in Nashville, he started courting the local country scene, and in 1966 released the country music exploitation movie The Girl from Tobacco Row, starring Tex Ritter. He had a religious epiphany in the early seventies, when he survived a plane crash, and now was dead set on spreading the word of the lord in his films. Not that his Christploitation movies were any less lewd and gory than his previous films. He made five four more films in the seventies, all of them with heavy religious imagery of death and hell and about the importance of Christian morals in the fight against communism. Ron Ormond was also a writer of esoterica and Eastern mysticism.

The three first-billed actors are Jackie Coogan, and the two guys who pick up Doreen and Grant in the desert, played by Allan Nixon and Richard Travis, despite the fact that the have little more than five minutes of screen time. All three were friends of Ormond, and probably did their roles practically for free for a good billing. Coogan was at the time just a washed-up kid star, and the two others were B movie bit actors. Although Travis did appear in over 80 films or TV series, and even got decent billing in a couple of other films. He appeared in the serial The Green Hornet Strikes Again (1940) and actually played the lead in Missile to the Moon (1958), and appeared in the small role of the general in Cyborg 2087 (1966).

Lyle Talbot does his wonderful narration on this film, and much like Jackie Coogan, Talbot was an actor who was seen as having his best days behind him, although Talbot was still very active, appearing on nearly twenty TV shows and close to ten films in 1953 alone. That was pretty much the story of his career, having over 300 credits in film or TV between 1931 and 1987. In later years he said that he never once turned down a role, no matter how small or bad. Stage magician and actor Talbot got called into Hollywood in the early days of sound cinema, when the studios needed ”actors who could talk”, and was quickly established as a ”matinee idol” and leading man of B movies, and was one of the founders of the Screen Actors Guild. His activity in the union angered studio brass, who quit offering him leading roles, and he instead transformed himself into a sought-after character actor for B films. In film, he is probably best known for having appeared in three Ed Wood movies: Glenn or Glenda (1953), Jail Bait (1954) and Plan 9 from Outer Space (1959).

Talbot worked on a few little-known semi-sci-fi films in the thirties, and was quite a pioneer regarding DC Comics. He played Commissioner Gordon on the second Batman film serial in 1949, Batman & Robin. He was also the first actor to play Lex Luthor in a live-action film, in the serial Atom Man vs. Superman in 1950, opposite the first Superman, Kirk Alyn, whose work we have covered in the review of the first Superman serial. He appeared in Untamed Women (1952) and Tobor the Great (1954, review), and had a recurring role in the film serial Commando Cody: Sky Marshal of the Universe (1953-1954). His last role was a small uncredited part in the sci-fi spoof Amazon Women on the Moon (1987). But he was probably better known as a fixture on television from the mid-fifties onward. Most fans would know him from his role as Joe Randolph in 74 episodes of The Adventures of Ozzie and Harry (1955-1966).

Paula Hill as Doreen isn’t really all that bad, considering the tepid lines she has to utter, she does lend the film a certain credibility as the gold-digging, chain-smoking blonde marrying for money. Sadly, this was her only major role. She appeared in about a dozen B movies, including The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1953, review), and transitioned into television, as many actresses, in the fifties, before she quit the business in 1958. She made a surprise return in 2000 in a bit-part as a Hollywood manager in the comedy Chump Change, starring writer-actor-director Stephen Burrows and ex-porn star Traci Lords.

Robert Knapp is also feasible, if not especially good, as the hero of the flick. Knapp was a staple supporting or bit-part player in about two dozen films and had around 50 appearances on TV between 1951 and 1972. Mesa of Lost Women was one of his two hero roles.

Tandra Quinn, the mute spider girl, is featured heavily in the film, and the movie is probably best remembered for her (unnecessarily) long dance scene in the taverna, and she was utilised heavily in the marketing of the movie. There was a short ad with her kissing Knapp, with the narration: ”Have you ever been kissed … by a woman like THIS?” – a shot that isn’t in the film. Quinn, born Derline Jeanette Smith in 1931 was a child dancer and model, and was pushed into acting by her mother, who had her auditioning for a number of film roles in the forties. She finally did get a seven-year contract with Twentieth Century-Fox in the late forties, but never had a chance to make a film. She was dropped quickly as someone at the studio though there was ”something wrong with her face”.

According to the afore mentioned interview by Tom Weaver, Quinn/Smith had a near-fatal accident with an apartment heater when she was two years old, which nearly burned off half of her face. The burns themselves were hardly noticeable by her teens, but the damage to the bone structure in her face lent her features an asymmetrical quality, which I think adds to her personal look, but apparently Fox didn’t consider her pretty enough. By 1950, then only 18 years old, she met Herbert Tevos/Schoellenbach, who swept her up in his Svengali-like way and told her she was going to be a star. In Tarantula, however, the dance scene was her only appearance in the movie. After the film was finished and canned, she was brought back a year later with most of the rest of the principal cast by Ron Ormond, who apparently saw much of the same feisty qualities in her that Schoellenbach had seen, and promptly made her the actual star of the movie, despite the fact that she had no lines. Someone from the team behind Neanderthal Man, released only weeks after this film, must have been around during production or seen some early screening of the film, since she was cast in another mute role, as the housekeeper/panther woman in that film. She did two other films in 1953, and then got married and quit acting. In her own word, she had been so beat down by years of rejection, that she had mental illness and had become a compulsive eater. In the interview she says that this she later lived a very happy married life, travelling a lot with her husband and becoming very interested in gold-digging, later became a nutritions expert and worked at one time for gold-mining company. She has a lot of laughs about her cult fame and her brief acting career in her interview with Weaver. I strongly recommend that you try and find the book.

Regarding the many, many mute roles in this film and other from the era, they have a perfectly reasonable explanation. Actors who played mute roles got paid less than actors with speaking roles, so you could get together a rather large cast without losing a lot of money by keeping them silent throughout the film.

Mesa of Lost Women actually contains a lot of interesting actors, but I’ll bore you out of your wits if I go into them all. But we should mention some of them. The short, rotund Chris-Pin Martin was a memorable character actor, often playing the same sort of Mexican stereotypes he does in this film. Let’s hope he didn’t have to say ”Ay caramba” in all of the movies. He appeared in over 140 films from the twenties to the fifties, including Rouben Mamoulian’s The Mark of Zorro (1940) and John Ford’s The Fugitive (1948). Mesa of Lost Women was his last role. Harmon Stevens only had seven film roles, and if you watch his acting in this film, it is obvious why. He had a bit-part in The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951, review).

George Barrows, as George the Male Nurse, was a prolific bit-part actor, and most of all one of Hollywood’s top gorilla men. He made most of his living playing gorillas or ape men in a suit of his own design. But he also had a number of roles outside the suit, and this one is probably one of his biggest. The man was built like a brick wall, and I suppose you had to have some stamina in those suits. We have encountered him before on this blog, as the robot monster in Robot Monster, see that review for more on Barrows.

Then there’s Dean Riesner as an Araña henchman. Riesner would go on to become a successful scriptwriter, and Clint Eastwood’s go-to guy from the late sixties to the late eighties. He collaborated on Coogan’s Bluff (1968), Dirty Harry (1971), Play Misty for Me (1971), and numerous other Eastwood films. He also wrote for Blue Thunder (1983) and John Carpenter’s patchy but underrated drama Starman (1984).

The two dwarves are played by two of Hollywood’s most prolific and talented short actors, John George and Angelo Rossitto. George was actually born in Syria as Tufei Filthela, and acted in close to 200 films from 1916 to 1961, including Lon Chaney Sr’s The Road to Mandalay (1926) and the masterpiece The Unknown. He also appeared in Island of Lost Souls (1932, review) and The Bride of Frankenstein (1935, review). Rossitto’s career spanned 60 years from 1927 to 1987 and he appeared in a number of great films, as well as many TV series. He was in Tod Browning’s controversial Freaks (1927), Cecil B. DeMille’s Sign of the Cross, and had small uncredited roles in a bunch of classics. A prolific sci-fi actor, he appeared in The Mysterious Island (1929, review), Invasion of the Saucer Men (1957), The Story of Mankind (1957), Brain of Blood (1971), Dracula vs. Frankenstein (1971), The Clones (1973), The Dark (1979), Galaxina (1980), and the film he will be forever remembered for – Mad Max: Beyond the Thunderdome (1985), where he made a huge impact as The Master.

And then there’s the lost women. First of all we have the two best friends in real life, Dolores Fuller and Mona KcKinnon. Fuller, of course, is immortalised (albeit unrealistically) by Sarah Jessica Parker in Tim Burton’s Ed Wood (1994), as Wood’s girlfriend. In real life, she was indeed that, but also Wood’s provider, associate producer, location scout, wardrobe manager and much more, as well as an actress. At the time she held up a steady job as a double for one of the stars in a popular TV show – a three day a week job, as he told – who else? – Tom Weaver in his book It Came from Horrorwood. She starred in Wood’s films Glenn or Glenda, Jail Bait and Bride of the Monster (1955, review). After that she engaged in her other career as a songwriter, best known for writing hits for Elvis Presley movies. Anything about Fuller should not be gleaned from Sarah Jessica Parker’s portrayal of her in Tim Burton’s biopic, as that portrait is not even remotely based on the real Fuller. As opposed to the movie character, Fuller was very supportive of Wood, his transvestism and his filmmaking. McKinnon, with whom Fuller shared a house at a time, appeared most of Wood’s movies, which along with Mesa pretty much makes up all of her acting credits.

Sherry Moreland had 20 credits, and appeared as the blind Martian girl in Rocketship X-M (1950, review). Katherine Victor was a multi-talented woman who worked as an animator, architect, actress and lots of other things. She was typecast in horror and sci-fi films in the fifties, and appeared in Invasion of the Animal People (1959), had the female lead in Teenage Zombies (1960), appeared in Creature of the Walking Dead (1965) and again played the lead in The Wild World of Batwoman (1966), credited as the 40th worst movie ever made on IMDb, and appeared in Frankenstein Island, which escapes IMDb’s Bottom 100 list by not having gathered the required 1 500 votes. In the eighties and nineties she made a career at Disney as a continuity coordinator and animation checker some of Disney’s lesser known films, but mainly on the company’s TV shows.

Suzanne Ridgeway was a prolific bit-part actor who appeared in everything from Citizen Kane (1941), one of the best films ever made, to From Hell It Came (1957), one of the worst films ever made. B movie starlet Margia Dean is claimed to have been one of the spider girls, although she vehemently denies it.

And that’s just the actors. The movie credits almost every artistic and technical staff double, since the artistic team got completely overhauled when Ormond took over the movie. Considering some of the talent behind the camera, it is almost unbelievable that the film looks as bad as it does – but it only goes to show that without a script, a capable director, and some amount of money and time, it is very difficult to make a good-looking movie. Some of the ”talent” involved only have a handful of other credits, but the two cinematographers, for example, are not to be sneered at. Although mostly involved in B movies, Gilbert Warrenton had been in the business since 1916, and was cinematographer on the brilliant and highly influential Universal horror-mystery dramas The Cat and the Canary (1927) and The Man Who Laughs (1928). Both films were directed by Paul Leni, and served as precursors, of sorts, of the Universal monster movies of the thirties (some may argue they were better than the Draculas and Frankensteins of the following decade, and I would almost be inclined to agree). In 1956 he filmed the below par jungle sci-fi film Jungle Hell, starring Sabu, and worked on The Atomic Submarine (1959), Flight that Disappeared (1961), the colourful Jules Verne adaptation Master of the World (1961), starring Vincent Price and Charles Bronson, and Ray Millands post-apocalyptic Panic in Year Zero! (1962).

The other cinematographer on the project was none less than the master Karl Struss, who won an Oscar for his work on F.W. Murnau’s Sunrise: A Song of Two People (1927), and was nominated for Rouben Mamoulian’s Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1931, review), Cecil B. DeMille’s Sign of the Cross (1932), Alfred Santell’s Aloma of the Seven Seas (1941). As if that wasn’t enough, he had his hands all over Robert Florey’s Hollywood Boulevard (1936), and Charlie Chaplin’s The Great Dictator (1942), as well as Limelight (1952). He was chiefly responsible for the amazing quality of the sci-fi horror film Island of Lost Souls (1932), and filmed the surprisingly good Rocketship X-M (1950). He went on to shoot several more sci-fis: She Devil (1957), Kronos (1957), The Fly (1958) and The Alligator People (1959).

Orville Hampton acted as dialogue supervisor, and IMDb also adds him as an uncredited screenwriter, which means he probably wrote the new script along with Ormond. He also wrote for Rocketship X-M, Red Snow (1952), The Alligator People, The Atomic Submarine, Flight that Disappeared, The Underwater City (1962), Space Stars (1982), as well as a number of sci-fi TV shows. Hampton was nominated for an Oscar. Wardrobe supervisor Oscar Rodriguez also worked on I Was a Teenage Werewolf (1957), How to Make a Monster (1958), The Phantom Planet (1961) and The Creation of the Humanoids (1962). Special effects man Ray Mercer worked on Return of the Ape Man (1944), Superman and the Mole Men (1951), as well as the following Adventures of Superman TV serial (1952-1953), Master of the World, The Beast of Yucca Flats (1961) and Panic in Year Zero!

Another thing that makes the film almost unwatchable is the music, if you can call it that. The whole film is engulfed in a butterfingered strumming Spanish guitar, accompanied by atonal banging on a piano (I’m not exaggerating – someone is sitting by a piano, banging for dramatic effect on seemingly random keys). At first I thought they had dragged some stage-hand who knew a few guitar chords into a recording studio, but it turns out that the music is actually written by Hoyt Curtin, who would garner fame for his compositions for a number of animations, including Jonny Quest, Scooby-Doo, Josie and the Pussycats in Outer Space, The Flintstones, The Jetsons, Battle of the Planets, Super Friends, Yogi Bear, GoBots and Smurfs.

For many years there was a theory going that Mesa of Lost Women would have been a lost Ed Wood movie, that Wood would for some reason have written and directed it under the pseudonym of Herbert Tevos and then been replaces, or that he might have produced it. The mistake is understandable, as so many Ed Wood staples show up both in front of and behind the camera. But in fact, there is no evidence that Wood had anything to do with the film. But Wood and Ormond were very good friends, and both were also friends of Bela Lugosi, so it is quite conceivable that Ormond was part of the posse of outcasts and misfits around Wood. As both were struggling filmmakers who needed to pinch a penny, and both needed cheap but reliable actors and crews, it is not that strange that they would draw from the same pool of people that they normally would hang around.

To give you an idea of the sloppiness of the script: spiders are constantly referred to as insects and hexapods (six legs), although the spider props nevertheless have eight legs. The proper thing to call them would of course have been arachnids and octopods. No explanation is ever given as to why Masterson decides to show up in the tavern. Wu is apparently both manservant to van Croft, who has no connection whatsoever to Araña, and at the same time Araña’s henchman, again this goes unexplained. Tarantella is “killed” at the tavern and the posse then leave without delay by car and plane, but somehow she still manages to get to the mesa before them. Despite the fact that Masterson is a feeble little man, and Phillips and George could easily have overpowered him, they never try to disarm him, even though they have plenty of opportunities. And so on and so forth.

Mesa of Lost Women is inept in every department, from writing to production through direction to acting, editing, cinematography and music. The dialogue is like something written by a 10-year old and the actors look painfully aware of it. The whole premise is baffling in its stupidity, and there’s not even any point in trying to point out the holes in the logic, because the whole film is a hole in logic. There’s no passion behind the movie that would redeem it, as in Robot Monster and the Ed Wood films. Whatever Schoellenbach was thinking, we will probably never know. Ormond hated the original film and probably just did what he could to try and make at least something out of it. Nevertheless, if you are a friend of bad movies, it is recommendable as a feast of crappiness. And I’ll admit, there are a few laughs in it. As for our spider girl Tandra Quinn, there’s no knowing if she might have developed into a decent actress, but at least she has the fire and charisma, and that dance scene, which she improvised, has gone down in bad movie history. But from what I’ve read, she was probably better off outside Hollywood.

This film is given the rare honour of joining the elect few that have garnered zero stars on my list of awful movies.

Mesa of Lost Women (1953). Directed by Herbert Tevos (Herbert von Schoellenbach) & Ron Ormond. Written by Herbert Tevos & Orville H. Hampton. Starring: Jackie Coogan, Paula Hill, Robert Knapp, Tandra Quinn, Harmon Stevens, Nico Lek, George Barrows, Allan Nixon, Richard Travis, Lyle Talbot, Chris-Pin Martin, Kelly Drake, John Martin, Candy Collins, Dolores Fuller, Dean Riesner, Doris Lee Price, Mona McKinnon, Sherry Moreland, Ginger Sherry, Chris Randall, Diane Fortier, Karna Greene, June Benbow, Katherine Victor, Fred Kelsey, Samuel Wu, Margia Dean, John George, Angelo Rossitto, Suzanne Ridgeway. Music: Hoyt Curtin. Cinematography: Karl Struss, Gilbert Warrenton. Editing: Ray H. Lockert, Hugh Winn, W. Donn Hayes. Set decoration: Ted Offenbecker. Makeup: Harry Ross, Paul Stanhope. Sound: Charles Clemmons. Special Effects: Ray Mercer. Wardrobe: Oscar Rodriguez. Produced by Melvin Gordon & William Perkins for Ron Ormond Productions.

9 thoughts on “Mesa of Lost Women”